Nnamdi Oguike

I didn’t realize that my baby brother’s ngente was close until Papa returned one afternoon on his motorcycle with a ram with large, twisted horns, black, and dreadful eyes and a thick white fur. As my father untied the ram, it gave a low-throated bleat and leapt off the motorcycle, but Papa snatched the rope in time, dragged the animal and tethered it to a shrub in our front yard. It was bigger than the one he bought for the last Tabaski celebration. As I skittered towards it now, it moved three steps backwards and charged forth.

“Look out, Bousso!” Papa yelled.

I leapt away in time. The ram broke loose and crashed on its horns, making deep marks in the ground. Papa dived at it and wrestled it down by its horns. His cap fell and his boubou was smudged with mud. I shrieked and ran into the house to call Maman.

“Maman! Maman! Maman!” I cried. “Papa is wrestling with a ram!”

Maman, who was breastfeeding my baby brother, yanked her nipple out of his mouth and hurried outdoors.

Papa had subdued the ram and dragged it by its horns into one of the outhouses that he had put up for rent since he became friends with a wealthy man in Dakar, who had many houses in Dakar, and lived with two wives in a mansion painted white and gold. The man’s name was El-Hadji Ousmane, and he became Papa’s client only after Maman became pregnant with my baby brother. Because of that, Maman said my baby brother brought good fortune. In a few months of polishing and remaking gold necklaces and bracelets for El-Hadji Ousmane’s wives and the wives of El-Hadji Ousmane’s rich associates, Papa changed the rusty roof of our house, replaced the cane chairs of our living room with brown upholstered chairs and a sofa, and built three outhouses for rent.

I am the oldest of my siblings—Fatou, Cheikh, and my baby brother—and Maman tells me my ngente was poor because Papa had just ended his apprenticeship to his master, and although Papa could fashion anything out of gold, he had no bellows of his own, no anvil,

no mallet, no money. So my ngente was almost no ngente at all. My family didn’t invite the neighbors because we had no lakh for them to eat and no bissap for them to drink. And the sheep that was brought for the naming ceremony—a bony, diseased runt—was bought on credit and it took Papa a year to pay off the debt.

According to Maman, things got better for our family when my sister Fatou was born. Papa had just set up his smithing workshop on the outskirts of Dakar, but not many people took notice of him. He made money polishing metal jewelry, and fashioning figurines and statuettes. Maman says Papa was so good he could shape brass or bronze or gold into any shape he wished. But the rich of Dakar did not yet know him then. For Fatou’s ngente, my parents got a black sheep. Although it wasn’t bought on credit and my parents invited our neighbors and some friends, my family survived after the ngente practically on credit. When my brother Cheikh was born, misfortunes struck Papa. Papa’s papa—my grandfather—became sick and died. He had barely been buried when Papa’s only brother and youngest sibling, Oncle Aliou, who was living with us at the time, took his things and went to Saly. He was the best storyteller in the world; even Maman fell for his stories and sat on the floor with us to hear him. He told us he inherited his storytelling gift from our grandfather, who was a griot. He wasn’t like Papa, who had no time for stories. Oncle Aliou once owned a boat he ferried people on to Italy for money but on his last trip on that boat, a storm split the boat in two and all passengers on it drowned except him. When he came to live with us, he had nothing: no boat, no livelihood, only stories. Maman said he had a disagreement with Papa. What it was about, she did not say. She said, “It’s what brothers do sometimes: they disagree.” Fatou said it’s because Oncle Aliou brought liquor into our house one night and Papa is a strict Muslim that doesn’t drink liquor. Maman said it wasn’t that. But on the morning before he left our house, I heard Papa yell at him, “Saly? You will not go to Saly! Never!” and then storm off to work. Before he returned, Oncle Aliou took his things and went to Saly.

We were so poor that Maman sold lakh on the streets. Maman says Cheikh’s ngente was more miserable than mine. Except our imam and our closest neighbors, my parents had invited no guests. But since everyone knew the ngente is held one week after a child is born, our house filled with unwanted children who waited endlessly for lakh and rice and jeered at us in disappointment.

It was the year after Oncle Aliou left us that El-Hadji Ousmane visited Papa’s workshop. He was tall and handsome and wore a gold wristwatch and necklace. Even the buttons on his clothes and the ornaments on his shoes were made of gold—so Maman says. The man brought a small box full of old necklaces and bracelets of gold and copper and brass blemished with patina. “These belong to my mother,” he said to Papa. “I want them polished. If you do well, I will bring more.”

Papa agreed. He did a good job and the man brought three more boxes. And since Papa could make exquisite things out of metal, he fashioned marvelous ornaments for the rich man and his mother and wives. It was the same month in which Papa met El-Hadji Ousmane that Maman became pregnant with my baby brother. So Maman believed that my brother came with good fortune.

When he was born, we were all carried away by his charm. Maman said none of us born in the house was as plump as he at our births. We didn’t have photographs of our faces at birth, but when Maman told you a thing was such and such, it was so. She knew all our presidents; she remembered how much a cup of lakh or milk and millet cost during the years of Senghor or the years of Diouf or the years of Wade. She didn’t forget as much as Papa, who sometimes couldn’t remember how much gold or money his debtors owed him, or who forgot to exact the punishments he pronounced on us but deferred especially if he was busy sketching a jewelry design. So we believed Maman when she looked at my baby brother and said, “Bousso, Fatou, Cheikh, you all looked too skinny when you were born—as if I never ate a thing when I was pregnant with you.”

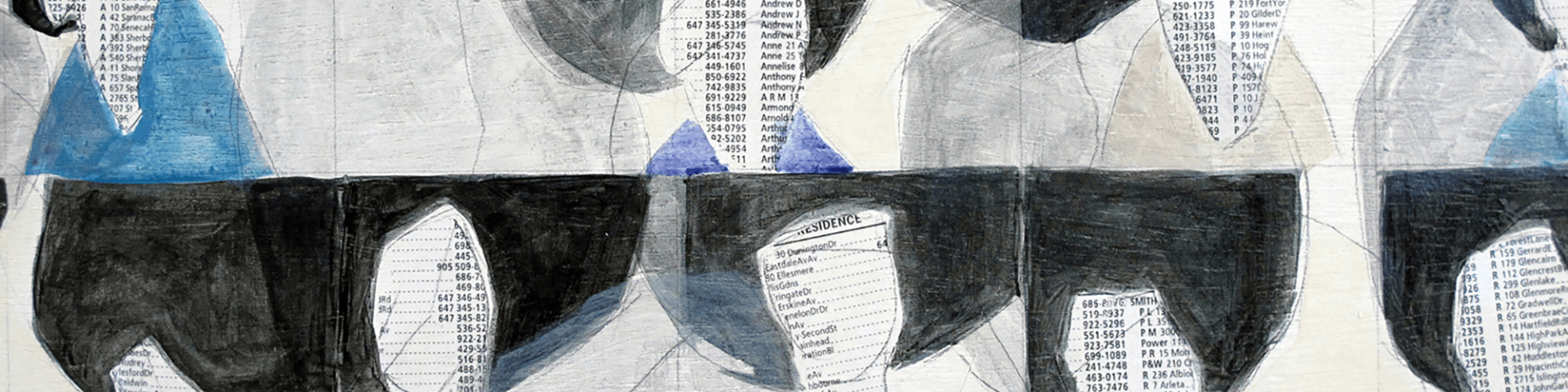

Tina Williams Brewer, Oar Up or Down: Angels and Ancestors, 2023. Textile- mixed media. Courtesy of the artist.

Fatou and Cheikh threw back their heads and bawled with laughter, but I was beginning to feel a little envy that my newborn brother might just have taken for himself all of the good fortune—enough for the four of us put together. But I loved him all the same. He had a thick tuft of hair on the top of his head as if an unknown barber had shaved the sides, leaving the big shock of hair in the middle. I liked to touch the hair, to feel the fluffiness of it, to smell the baby oil that Maman smeared on it. I loved to feel the plumpness of his cheeks and the blub- ber of his neck. During mealtimes, I carried my food to eat beside him. But because it had been a long time since Cheikh’s miserable ngente, I had forgotten about ngentes, and did not know that one was at hand until that afternoon when Papa returned home on his motorcycle with the fattest ram I had ever seen.

*

Life had become good for us—much better for us than for most of our neighbors—but I couldn’t understand why Papa went the length he did to arrange my baby brother’s ngente. After he had brought the big white ram, he announced to us, “Oumar the painter is coming to paint the house.”

I was amazed. Our house had known no paint all its life. Apart from its old rusty tin roof that Papa had changed, nothing else had been changed in the house. Its large slatted wooden windows were still intact, the knobs on its wooden still turned, the cement floor was still smooth, and we had never thought it was a bad house. Not even when we saw the new posh houses in Dakar—houses prettied with colors, like giant birthday cakes. But now Papa reminded us that our house needed a face-lift.

“Oumar must paint all the rooms and the outside. Everywhere must look new. The walls, the ceiling, the windows, everything,” Papa added.

I was also surprised when Babacar the carpenter popped up in our house later that afternoon with his box of tools, to mend our wobbly chairs and stools and the broken slats of our windows. Our house throbbed with the sound of his hammer. Cheikh liked the noise and danced and yelled in sync with the hammer. Maman took him and Babacar to task for waking my baby brother. The baby bawled out and Babacar put down his hammer and sang for him.

“You are scaring him with your raspy voice, Babacar!” Maman cried.

Babacar stopped singing and said, “Sorry, Madame, I am better at playing the guitar. I’ll bring my guitar to the boy’s ngente.”

“Bring whatever you will, Babacar, but don’t make my baby cry like this on that day,” Maman said and carried my baby brother away into one of the outhouses.

When Babacar resumed his work, Fatou and I stuffed our ears with our forefingers but Cheikh went on singing and dancing to the tai- tai-tais of Babacar’s hammer. We yelled at him, “Cheikh, you will get a headache!”

But we were soon diverted by the arrival of Maman’s sister, Tante Maimouna. She was big and heavy whereas Maman was slim, dark, whereas Maman was light-skinned, chatty whereas Maman was taciturn, and quick-footed whereas Maman was slow. She had a shop in Marché Sandaga, where she sold grains.

A taxi brought her. As soon as I and my siblings spotted her dark face and big arms in the taxi, we ran out to meet her. She squeezed her body out of the back door of the taxi and took us in her arms, Fatou first, Cheikh second, me last. She pressed our heads into the softness of her breasts and shrieked in Wolof, “Na ngeen def? Have you peace?”

“Jaam rek,” we replied. “Peace only.”

“You are a big boy, Bousso,” she said to me. And to Fatou, “Look at you, Fatou. Such a pretty girl.” And to Cheikh, “Your teeth are all missing, Cheikh. Don’t worry, they’ll grow back looking finer.” She looked towards our house. “How is your maman?”

Maman slowly came out of the outhouse, my baby brother in her arms. She stood in the doorway and smiled.

“Maimouna,” she called.

Tante Maimouna hurried towards her with a hacking laughter. Her feet made loud thuds on the ground.

“Khadidiatou, my sister!” she said. “Na nga def?” “Jaam rek,” Maman replied.

Tante Maimouna took the baby from Maman and rocked him in her arms. “He is so big! What are you feeding him? Lakh?”

“No! Just my breast milk,” Maman said, laughing weakly. “Are you eating at all?”

“I am.”

“No, you’re not. You are thin like a mosquito.”

The taxi driver had set Tante Maimouna’s bags on the ground and was murmuring and fussing around his taxi. He was a very lean man with a long torso, and he wore an undersized brown shirt that hung way above a small, hairy waist. Cheikh trained a finger on the man’s waist and giggled.

“Shut up, Cheikh,” I muttered.

But Cheikh doubled down on his laughter until the man saw him and pulled his trousers up to cover his waist. “Spoilt children,” he said.

“What is he saying?” Tante Maimouna said to me.

“Please give me my money, I want to get away from here,”’ the man said.

Tante Maimouna gave him a stern look, shook her head, and slipped out a few franc notes from her purse, “Bousso, take this to that stick insect over there!”

The driver snatched the money from me and muttered about elephants who ride in taxis when they ought to be in trucks. He slammed his door and drove off in a cloud of smoke.

My aunt brought lots of hibiscus leaves for bissap, a bag of millet for lakh, and had cooked some thiéboudienne. As soon as she had settled into our home, we pounced on her delicious rice and the sweet bissap she had made.

While we were gobbling Tante Maimouna’s rice, Papa’s sister, Tante Aissatou arrived in her taxi. She owned the taxi, and the taxi driver waited for her for as long as she stood in our yard for pleasantries, and she didn’t pay the driver a franc. And the man carried the bag of rice and the bag of vegetables that my aunt had brought and set them down in our house.

“Don’t forget to come and pick me in two days’ time at five in the evening,” Tante Aissatou said.

“Pas de problème,” he said, bowed and left.

Our house was full now with food and my aunts’ chattiness.

Then that night, when Papa returned from his work, he announced with a smile that El-Hadji Ousmane would be attending my baby brother’s ngente coming up in two days. El-Hadji Ousmane of the boxes of gold watches and jewelry. El-Hadji Ousmane who had two wives. El-Hadji Ousmane who wore gold buttons and shoes adorned with shiny gold. El-Hadji Ousmane, whose connections had turned Papa’s life and enterprise around.

“Yes, he is coming,” Papa said. “I spoke with him on the phone today. He agreed. It is a big honor that he is coming.” It was a rare thing to see Papa smile.

“This boy has plenty of luck!” Tante Maimouna said, bobbing with laughter, fanning her big body with her hands.

Tante Aissatou, who sometimes behaved like a fortune teller, said to Tante Maimouna, “I told my brother about what I saw in Khadidiatou’s womb—a boy with hands clenching gold. I said so. Ask my brother.”

Papa nodded and said, “Yes. Aissatou told me so.”

“And I told Khadidiatou too,” Tante Aissatou said. “Long before she even conceived this boy. I don’t know if she remembers it. It was at Bousso’s ngente.”

“That ngente where there was no food?” Tante Maimouna said and laughed.

“It was a miserable ngente,” Maman said, shaking her head. “We had nothing. We invited nobody except the imam.”

“But I came,” Tante Aissatou said.

“I came too,” Tante Maimouna said.

“Remember, Khadidiatou, I told you that your fourth child will come like a prince. There is no child that crossed your womb that I didn’t see their destiny.”

“I remember all you said,” Maman said.

I didn’t like Tante Aissatou very much. I hated the pride with which she spoke, as if she saw everybody’s future. I didn’t like how she gazed at me sometimes and said, “I see envy in your eyes.” I felt envious of my baby brother and the good fortune of his forthcoming ngente. The rest of us children had poor ngentes. Now he got the biggest ram for his ngente. And one of the richest men in Dakar was coming to the ngente. I was full of envy. Although Tante Maimouna fondled my head and those of Fatou and Cheikh and said, “Don’t worry, your small brother’s ngente will make up for your poor ngentes,” I wasn’t consoled. I just wished we could postpone my baby brother’s ngente till mine was redone with the best lakh served, the biggest sheep slaughtered, and a sumptuous feast prepared.

I didn’t voice my thoughts, but I was glad when Cheikh, who had the most miserable ngente in our family, said, “Papa, Papa, please do another ngente for me and Bousso.”

My aunts burst into laughter. Maman said the ngente was not for our baby brother alone but also for the rest of us. But Tante Aissatou, acting like one possessed by a spirit, took Cheikh’s palm, smiled into it and said, “You will be rich, Cheikh.” Upon which Cheikh began to bob on his feet, giggling as if he had gone crazy.

Tante Aissatou took Fatou’s palm and said, “You will be happy, Fatou.” Fatou grinned and twirled around, breaking away from my aunt. “Give me your hand, Bousso,” Tante Aissatou said.

I shoved my hand in her big palm and looked away. “Let go of envy,” she said to me.

I pulled away from her and sat in the fork of Papa’s legs on his upholstered chair. He fondled my hair as he chatted with Tante Maimouna about Oncle Aliou.

“Have you called Aliou?” Tante Aissatou interrupted.

“I will not talk to Aliou. Never!” Papa said, his face like a fist. “Ngente is a family thing. Aliou should come. It’s been over two years since your disagreement. I will call him.”

There was a long silence in the room before Tante Maimouna changed the mood of the room with talk about her long list of suitors, all of whom turned out to be frauds. We all laughed except Papa.

“Sometimes I feel as if someone put a curse on me,” she said and bobbed with laughter. “I’m losing hope that I’ll be able to marry in this life.” She leaned over to Tante Aissatou and said, “What do you say, our seer?”

“The same thing I said to you the first day we met,” Tante Aissatou replied. “Nobody put a curse on you, Maimouna. Be at peace with yourself.” Tante Maimouna gave a shrug and made to say something, but Tante Aissatou turned to Maman and said, “I’m hungry now. I would like some rice and a cup of bissap.”

Maman rose, her head almost grazing the roof, as if she had grown taller just days to my baby brother’s naming ceremony.

*

Because Tante Maimouna was in our house, we had more food than before. The next morning, she cooked so much millet and poured so much soured milk and sugar that I wondered if she was cooking for a crowd. And her lakh was richer and sweeter than Maman’s lakh. Tante Maimouna prettied her lakh with banana and coconut and apple and raisins, and she was happy to give us more.

“Eat more, my children,” she said. “Don’t be like your maman who eats like an ant. Eat and grow big.”

Fatou ate like Maman and was full after Tante Maimouna’s first serving, but Cheikh went on eating his third serving until he nearly passed out.

We fell into a deep sleep after Tante Maimouna’s meal. And when we woke up, we found out that she had cooked lunch. She loved to cook, and she cooked better than Maman and Tante Aissatou. The last time Tante Aissatou brought us rice she had cooked, none of us in the house liked it. Cheikh, who ate anything in the world, rushed outside and puked because the meat was still raw. Fatou could have cooked better rice than Tante Aissatou.

But this time in our house, she left all the cooking for Tante Maimouna and devoted herself to my baby brother, cleaning him up or rocking him to sleep. She brought him a gorgeous binbin with beads that glowed a gentle lemon green in the dark. She hung it around his neck to ward off bad spirits. She carried him in her arms and recited verses of the Koran and spoke of the gold she had seen in his hands and of the prosperity that he would bring into our house.

While Fatou and Cheikh fed the ram, I went to eavesdrop on Tante Aissatou. I heard her praying for my family. She prayed for Allah to surprise us with good things. She prayed for Papa to be the richest gold- smith in Dakar, for Maman to have more children, for Tante Maimouna to find a man of her dreams, and for Oncle Aliou to stop selling idols to tourists. She prayed for us children—from me to Fatou to Cheikh and to my baby brother. And then she prayed for my brother’s ngente: “Grant us, O Allah, the ngente of peace.”

*

On the morning of the ngente, Papa brought the barber Moustapha to shave my baby brother’s head. The baby bawled all through the haircut. When Moustapha finished, and Papa paid him for the job, my brother

looked smaller in my eyes. Tante Aissatou carried him to bathe and dress him in his special clothes for the ngente.

Our house smelled of fresh paint and of Tante Maimouna’s lakh and thiéboudienne.

Souleymane the photographer soon arrived on his bicycle and started taking photographs. Cheikh fluttered around the camera like a moth to a light bulb. Fatou feared it because it was a wonder how people and things sneaked into the camera and came out on paper. I loathed the camera because I looked uglier in my pictures than in Maman’s standing mirror. But I and Fatou and Cheikh posed for pictures today because it was my brother’s ngente. Papa and Maman posed for theirs, Maman carrying the baby. My aunties joined.

Our imam arrived soon afterwards, and Papa ushered him into our living room. He was short and old and one of his eyes had turned the colour of milk. I used to think he never liked me, for he always didn’t answer my greetings; it wasn’t until Maman told me to shout my greetings to him that I realised that he was going deaf. With him presiding over any ceremony, everyone who talked to him shouted as if they were talking to someone in another town.

After the imam settled in our house, a great unease seized Papa. I heard the adults asking one another, “Why has the man not arrived? What is keeping him from coming? Has anyone called him?” Every now and again Papa took out his small mobile phone, pressed numbers, and stuck the phone on his left ear.

“He is not picking!” Papa said.

He dialed again and shook his head. A small crowd surrounded him in the front yard, speaking gently to him. His face darkened with rage. “But he promised me that he would come!” he roared. “And he is not even picking his phone!”

Whenever Papa sounded like that, someone had offended him. But it was not too long before I realized that he was vexed because El-Hadji Ousmane, who had promised to attend this ceremony, had not yet come.

Every now and then Papa went to the imam and yelled a plea for more patience. The imam was patient. But his patience could expire any time soon because he had many appointments at the mosque or in the city.

Now our living room was full of guests. Outside, a crowd of relations and neighbors and children sat or stood waiting for the ngente to begin. Tante Maimouna served lakh to them. But there was an air of something amiss in the place and more guests poured in as if to choke our yard.

Then there was the commotion of the arrival of a big man. We heard the clunk of car doors and the tua-tua of car locks. El-Hadji Ousmane had arrived, I thought.

But the man who walked into our front yard was nothing close to my expectations. It was Oncle Aliou—Oncle Aliou who left our house after a disagreement with Papa, Oncle Aliou who told stories like no other person we knew, Oncle Aliou from whom we had never heard for nearly three years, Oncle Aliou who, according to Tante Aissatou, was selling idols in Saly.

I and my siblings ran to him and jumped on him shrieking wildly because of all my uncles and aunts he was the happiest to be with. He brought loads of stories about tourists from America and Europe and Australia and other parts of the world we had never heard of in our lives, tourists bored of their own countries but happy to watch the sea roll to and fro on the shores of Saly. I threw my arms and legs around Oncle Aliou, and he spun around on his feet. Fatou jumped on his back. Cheikh tottered around the man’s thighs.

“Na ngeen def?” he greeted.

“Jaam rek,” we replied. Then we asked, “What did you bring for us?” “Wait until you hear my stories,” he said. “I met a tourist who is a magician from Casablanca: he had a carpet that could fly. I ran into a snake charmer from Ouagadougou: he snapped his fingers and his snakes crawled out of his wooden box, and when he whistled a song they all fall asleep, and he put them back in the box. And then I found the most beautiful woman from Yamoussoukro. You just wait, I will show

you her picture and tell you her story.” “Tell us now,” Cheikh said.

“Tell us now,” Fatou said.

“No,” I said. “Night is the best time for stories.” “Night is the best time,” Oncle Aliou agreed.

I couldn’t wait.

Papa came out on our front steps and my uncle went up to say salaam aleekum and hug him. He had a car now—perhaps he had become richer than Papa. He looked Papa in the eyes and stretched out his arms towards him. I could not understand why Papa did not hug him as fast as Maman would have if he were her own brother. Maman says Papa didn’t use to be like that before he became a smith; she says working on metals turned Papa’s heart over the years into something tough and sometimes hard. Just like the way he behaved the day his papa, my grandpa, died: I and Fatou and Maman were howling our hearts out as his body bound up in a cloth was borne on a wooden stretcher, but Papa looked on among the surging crowd without a teardrop in his eyes.

Papa was just like that now in Oncle Aliou’s presence, and for a moment it felt as if my uncle—just like my grandpa—had died.

I pulled Fatou and Cheikh’s arms. “Let’s go and see Oncle Aliou’s car outside.” They agreed, and we traced our way through the crowd to our uncle’s car now coated with a film of dust as if it had weathered sandstorms through deserts. It looked new, a Toyota car whose tires were podgy like Tante Maimouna’s fingers and whose seats looked fresh and clean like Papa’s sofas on the day he bought them. We ran our fingers over the car, painting our faces with the dust on its body, giggling with mirth. We couldn’t touch our faces with dust from Tante Aissatou’s taxi—an old groaning Mitsubishi both of whose rear lights were blind and whose seats had gashes in them as if a butcher cut them with a cleaver. We wiped the dusty windows, and I saw on the dashboard a figurine of brawny Senegalese wrestlers locked in combat. Cheikh said he would ask to take it. Fatou peeped and spotted a photograph of a comely woman, tall like Maman but with younger eyes.

As we peeped, Papa and Oncle Aliou came to the car in a happier air. “This is my car, brother,” my uncle said. He pressed a button on his key and the car tua-tuaed again. He opened the doors for Papa to look in. Papa looked briefly, shook my uncle’s hand and returned to the house. But I rushed into the car. And Fatou scrambled in. And Cheikh. And two of the neighborhood children. The smell of leather filled my nose, and the plush aspect of the car became another ngente for us. My uncle turned on the car stereo and loud music poured out. Youssou N’Dour. We danced and celebrated in the car until Oncle Aliou said, “All right, all right, children. Let’s go. We will be back after the ngente.” We had almost crossed the doorway into our living room when a man in a voluminous white boubou hurried into the compound. The crowd cheered him because he was the man we had all been waiting for. Papa surged outdoors to greet El-Hadji Ousmane. He looked like a king in our compound and all eyes, smiling, gazed at him as he exchanged greetings with my father.

Tante Maimouna bobbed out of the house, but as soon as she saw the man she stopped limp as if someone struck her with a stone. Tante Aissatou came and took her away into the house. She was breathless as if she would faint. She drank water and bissap and lay on a bed for a while. The mishap contained, my brother’s ngente began. It was the most prosperous ngente we had known. Papa and our imam met to discuss my baby brother’s name, and they agreed on Ousmane.

The imam fondled my baby brother’s shaven head, said a prayer, and then leaned over to his ears and called him the name Ousmane, and we clapped and sang and celebrated. Souleymane flashed his camera lights. Babacar brought in his guitar and played. We clapped and danced, and everyone said he should have been a musician, not a carpenter.

The ram was immediately slaughtered to make a feast for the guests. Even before now, Tante Maimouna had cooked a sumptuous thiébou- dienne, which was now doled out in large bowls. Everyone who came for this ngente was certain to eat as much as their stomach could carry— unlike the miserable ngentes that the rest of us in our family had. And El-Hadji Ousmane had, in the spirit of the ngente, dropped three wads of money for his namesake and a currency note for each kid in the crowd.

As for Tante Maimouna, her strength and energy came back. It was in the night of the ngente, hours after our guests had gone, that we understood what had happened to her earlier in the day. She had felt an unusual feeling for El-Hadji Ousmane.

“It felt as if he put a spell on me,” she said. “As soon as I saw him I felt light in the head. My feet became weak. I almost fell. Then I went into the house, drank water, and lay down. I have never felt such happiness before. I think I’m attracted to El-Hadji Ousmane. I haven’t felt like this before. What do you think, Aissatou?”

“Nobody put a spell on you. Be at peace with yourself, Maimouna,” Tante Aissatou said, and then asked for some of the grilled ram from Maman.

But now I saw Fatou and Cheikh dragging Oncle Aliou’s arms towards the abutting room asking him if it was true what Aunt Aissatou had been saying: “Is it true that you sell idols to tourists?” I felt like shushing my siblings for asking that when I heard my uncle say, “No, not at all—I don’t sell idols. Who told you that? I sell art. Just art. Like the wrestlers you saw in my car. Things like that. And tourists buy them. Lots of them. Now come around, everyone. Bousso, Khadidiatou, Maimouna, I have wonderful stories to tell this night. I will start with the story about the magician from Casablanca. And then about the snake charmer from Ouagadougou. And then I’ll wrap up with the story about the woman from Yamoussoukro I want to marry.”

I hurried towards my uncle. But not only me but Maman also. And Tante Maimouna. And Tante Aissatou. And halfway through my uncle’s spellbinding stories—after I’d given up on Papa joining us—he walked in, baby Ousmane in his arms, to hear my uncle’s marvelous tales.