by Jamal Mahjoub

The images in the news report feel all the more shocking for how familiar they are. These are the same streets I had once walked along as a child. My uncle Moneim would take me by the hand and lead me around, proudly introducing me to everyone in the neighbourhood. We would stop at the little corner shop where I might get a paper twist of boiled sweets, or drop by the man who kept goats where I would ruffle their floppy ears.

I enjoyed spending weekends at my haboba’s house in Khartoum North, which back then was a simple place of mud walls and poor sanitation. They cooked on charcoal stoves made from old jerrycans. I can remember the sizzling aubergine slices and the kisra hot from the griddle. The old string beds were arranged around the yard and I would fall asleep under the stars, listening to my grandmother and the other women talking amongst themselves in soft, low voices.

Now that place was a hellscape of burned-out cars and bullet-ridden walls, the scorched ground dotted with blackened patches. Newly liberated by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the streets appeared pockmarked with shell craters and rubble. The dazed inhabitants spoke of being terrorised by the men with guns—the Rapid Support Forces, or RSF; the Janjaweed, as they are commonly known. The horror that raged in Darfur twenty years ago had finally reached the capital and turned this humble neighbourhood into a fierce battleground. There was no guarantee that the peace would last but the relief was palpable in the faces and voices of the people on camera. They had suffered a year of abuse, faced threats of violence, rape, and murder. The RSF took what they wanted and killed anyone who stood in their way.

The horror that raged in Darfur twenty years ago had finally reached the capital and turned this humble neighbourhood into a fierce battleground.

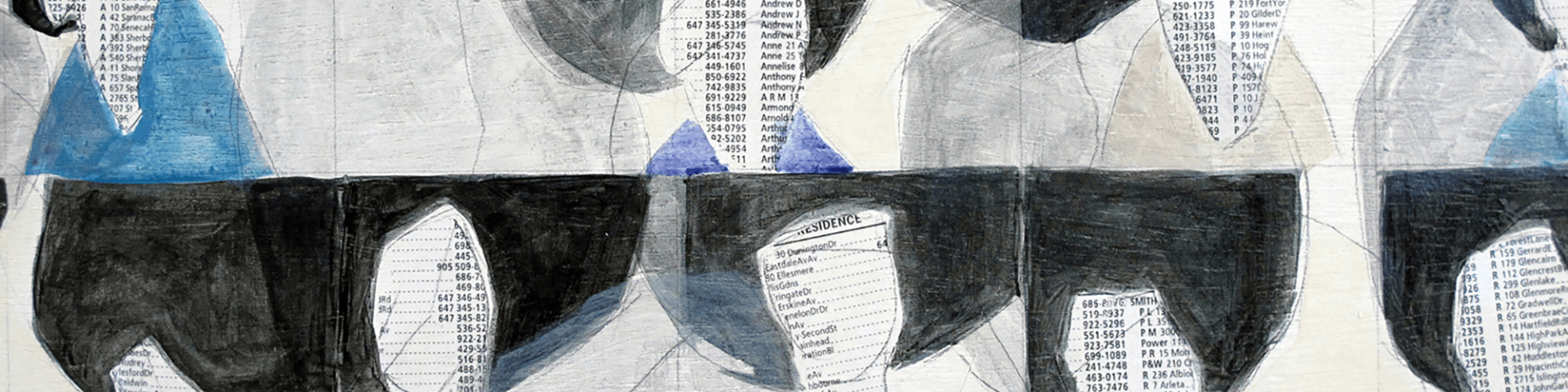

How could this happen—we asked ourselves over and over. How did a functioning, if struggling, country collapse into mayhem and ruin? During the first few months of the war, back in April 2023, we all looked on in horror and incredulity as the city we knew and loved began to crumble before our eyes. Thick palls of black smoke hanging over the skyline told us this was like nothing we had ever seen before. With power cuts and communications breaking down we tried desperately to contact friends and family. How could this violence bring anything but disaster? People relayed pictures of famil-iar homes that had been invaded, windows and doors smashed, their belongings trashed or stolen. Military helicopters skimmed by over the trees as gun battles raged from street to street. The airport, the palace, the national bank, the old Souk al-Arab, all lay in ruins, blown apart, burned to the ground. It didn’t matter who was doing the firing, the casualty was always the city.

In the beginning it was a spectacle, occupying the media sphere as news outlets raced to cover the dramatic evacuation of foreign nationals. British military planes and American helicopters swept in to rescue their citizens. Many of these were Sudanese who had fled the country over three decades of the Bashir regime. They had acquired British or American citizenship while in exile. Now they were being rescued from their old world. This was a sign of the new face of Sudan—a fractured nation divided along many fronts, but also between those within and those without. It was quite surreal to watch people marching up the ramps of the Royal Air Force C130 transport planes to be flown back to the safety of Britain. A bizarre echo of the nineteenth century, when the Relief Expedition raced to Khartoum to rescue General Gordon and his beseiged battalion in 1883. Once the evacuation was complete, the story simply dropped off the front pages. The world’s attention moved on; our problems were no longer of immediate interest. Outside observers laboured to classify what was happening. Was this a power struggle between two generals? Was it a civil war? The distinction is ultimately irrelevant. It is a watershed. An existential struggle for the very soul of the country. It marks the passing, of not just an era, but an entire phase in Sudan’s history as an independent nation.

Outside observers laboured to classify what was happening. Was this a power struggle between two generals? Was it a civil war? The distinction is ultimately irrelevant.

A Nation at War with Itself

The Khartoum of my childhood in the 1970s was less a metropolitan city than a sleepy, provincial town. A quiet, low-tech kind of place, with old Hillman taxis and knock-kneed donkeys stuttering along the road. The frail umbilical cord of the Nile connected us to the world, winding its way north across vast swathes of desert, towards Egypt, the Mediterranean—or the “Middle Sea” as it is in Arabic—and all that lay beyond.

We lived a simple life. Like most people in the middle class, we were not wealthy. Both my parents worked tirelessly and argued incessantly, usually about money. But we were not wanting for anything. The house we lived in was a simple one-story villa through which the dust blew freely. The cars we drove were old and troublesome. Entertainment was provided by a handful of open-air cinemas that showed films that were generally a few years out of date. Less Hollywood than Cinecittà, more Shaw Brothers than Warner Brothers. Italian films with shaky editing and bizarre dubbing. Egyptian comedies and sentimental dramas. Big Bollywood dramas that combined high jinx action with song and dance routines. We were at the centre of a cultural crossroads that allowed the world to flood in from east and west. Such influences could, with a little imagination, be interpreted as modern echoes of the ancient world, with the confluence between east and west made manifest in the figure of Apademac, the lion-headed god carved into the side of the Nubian temple at Meroë. It has the body of a snake rising out of a lotus flower. A figure that to me represents the key to a rich and diverse history that has largely been lost.

Looking back at that time now, it’s as though we were immersed in a dream, unaware of what was actually going on around us. There was, after all, a civil war in the South of the country. Far enough away for it not to be a threat to our safety and security, but serious enough to contain the seeds of our undoing. It was a war about discrimination, about racism and inequality. The Northerners were prejudiced against the Southerners. They referred to them casually as ’abeed, meaning slaves, a term inherited blindly from the past that had never really been challenged. The people of the South had darker skins, they wore tribal scars on their bodies and faces. All of this could be traced back to a slave trade that had lasted for centuries. The first manifestations of conflict came early, even before independence was announced in January 1956. It took decades before Southerners were included in politics, academia and the media, and even longer for them to be accepted. The discrimination was symptomatic of a system of governance that was centred around the capital. Anything beyond that was deemed of lesser importance. This disregard is key to understanding where we are today. This centralised form of government dated back to the half century of British rule, and before that to the Ottomans, who invaded the country in 1820 in the name of Muhammed Ali Pasha, the man who ruled Egypt as his own fiefdom.

We were brought up with the belief that we all had a part to play in the building of the nation. At school we had a choice between studying biology or physics, which would determine whether we were to become doctors or engineers. My father’s generation spanned the transition from the jointly ruled British-Egyptian Condominium to independence. They inherited the task of creating a nation out of that disparate collection of peoples who happened to be framed within the country’s borders. My father’s family was not wealthy—my grandfather was a cook on Sudan Railways, but he was sent to Britain at the age of twenty-four to act as Student Officer for the men and women who were being sent to study abroad. This meant that many of his closest friends, the people who would gather in our house to spend the evening drinking and discussing politics late into the night, were the first generation of ministers, ambassadors, professors, deans, and chancellors. They were all personally committed to the task of creating Sudan as a nation and they passed that sense of responsibility onto us.

The greatest challenge facing that generation was an imaginative one: how to create a nation united by a common sense of purpose and shared destiny from a diverse population that was distrustful of its fellow citizens changing centuries of habits, prejudice and tradition, replacing ethnic, religious and regional loyalty with political affiliation. There were bumps along the way. Civilian rule was all too often disrupted by military intervention. As children we became used to being woken early in the morning by the sound of artillery in the distance. Martial music playing over Radio Omdurman for hours told us that another coup d’état had taken place. Some were short-lived while others lasted years. Successive military interventions short-circuited the country’s political evolution. Activists and opposition leaders were executed, or would vanish into prison or exile for decades.

Martial music playing over Radio Omdurman for hours told us that another coup d’état had taken place.

Civilian resistance to military rule asserted itself most notably in the popular uprisings of October 1964, April 1985 and, more recently, in November 2019. In all of those cases, the initial optimism and euphoria were eventually extinguished by military intervention. The same happened in October 2021. The current fighting, with the accompanying ethnic murder, rape and pillage are evidence of the failure of that collective project.

The Centre Cannot Hold

Sudan has always struggled to find its political centre of gravity. Political ideology rarely overcame the fierce ethnic, religious and tribal bonds that traditionally dominated. The military saw civilian rule as a threat to its authority. For much of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Khedives who had ruled Egypt since the early sixteenth century saw Sudan as rightfully theirs. They were a military dynasty whose authority rested with the Sultan who would appoint governors for all his provinces. Such authoritarian rule rode roughshod over the complex web of cultural, ethnic and political diversity that laid just beneath the surface.

One key factor in governing such a vast country (until 2011, Sudan was the largest country in Africa, with a total area of 2.5 million km²—larger than all of Western Europe) is distance. At independence in 1956, the country inherited a set of borders from its British colonial rulers that was less a definition of a newly born nation than a demarcation of the limits of other European powers pressing in from all sides. Centralisation meant that the further away from the capital you were the less your concerns mattered. It was easy to ignore problems and hope they would just go away. Instead, this created resentment that only grew over time.

The greatest problem was the North-South divide. Throughout the fifty odd years of British rule, contact was prohibited in an effort to end the slave trade. All travel and trade was forbidden. This only increased the distrust. Centuries of slavery had left Northerners feeling superior to their Southern brethren. Ideas about unity and nationhood only succeeded for short periods, hindered to a large extent by racism and prejudice. The people of the South had darker skin and wore tribal scars on their bodies and faces. They were animists, or Christians at best.

Ideas about unity and nationhood only succeeded for short periods, hindered to a large extent by racism and prejudice.

The First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972) emerged from this very sense of inequality between north and south. It lasted for almost twenty years. To the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, the aim of the war was not seccession, but to unite the country under the very principles upon which it was founded. Over decades, this changed. By the time of John Garang’s death in 2010, secession had become inevitable. It was a fateful blow to the country and in many ways marked the road to today’s catastrophe. Natural disasters, such as floods or famine, left the peripheral regions vulnerable. Their problems were often largely ignored, perhaps most notably in Darfur, an area the size of Spain with a population today of eleven million. It has a rich historical heritage. The Sultans of Darfur once lived in sumptuous palaces, once described as a Sudanese Alhambra. Darfur lies at the centre of the continent, an equal distance from the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea. The Sultanate evolved out of intermarriage between nomadic herders and sedentary farmers. The two groups lived in relative harmony until around thirty years ago when climate change and desertification began to encroach on their annual migration patterns, increasing ethnic tensions.

The war in the South was a low intensity conflict taking place in the bush far away from the seat of power and the urban elite of the capital. In its second phase (1983–2005), beginning in the early eighties, the focus of the war was control of the newly discovered oil reserves. The government activated ethnic tensions by arming a local militia called the Murahileen who were tasked with clearing the area around Bentiu and Rumbek in Upper Nile Province for the Swedish oil company Lundin. The resulting violence was horrific. Civilians were rounded up and burned alive in cattle cars. That case has only now, after some forty odd years, reached the Swedish courts. In the early 2000s, the strategy of weaponising ethnic division for political gain was again applied, this time in Darfur. Out of that the Janjaweed, emerged; the “devils-on-horseback”—a militia that would later morph into the RSF. With the blessing of Bashir’s government, they car-ried out a genocidal campaign of rape and murder, razing villages to the ground, transforming counter-insurgency into ethnic cleansing.

The violence drew a huge amount of international interest. Hollywood celebrities lined up to denounce the violence and call for justice.

The International Criminal Court in the Hague issued arrest warrants for high-ranking government officials, including the president. Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the Chief Prosecutor of the ICC at the time, declared that Darfur was a metaphor for a world gone bad: “If we succeed, Darfur will be like Argentina; not perfect, but at least people are not killing each other. If we fail, in twenty-five years the world will be like Darfur.” Moreno-Ocampo’s words now seem prescient. The secession of the South (2011) marked not a new beginning, as some may have hoped, but rather the beginning of the end. More division now seems likely to come with the great monolith fragmenting into smaller units. There is no guarantee that this will bring peace, even though it is probably a more practical model than the original. There was once talk of adopting some form of federalism to provide a more workable model of governance for a country so large. But the appeal of retaining the country as one unit seemed irresistible, primarily to the old colonial rulers, who saw borders as a means of maintaining their leverage, and then to successive governments.

Birth of a Nation

In 2007, I returned to Khartoum after more than sixteen years away. It was an emotional moment. My father had been forced into exile by Bashir’s repressive regime. He had been running a newspaper at the time and was given the choice of going to prison or leaving the country. He chose exile and remained in that state of limbo until a heart attack ended his life. He swore he would never set foot back in the country while Bashir was still in power. Yet there I was, defying his wishes with no clear idea of what I would find. It was the start of an odyssey that would culminate ten years later in a book on the city and the country’s complex evolution, A Line in the River (2018). I travelled there not knowing what to expect and found a country transformed in many ways. I rediscovered old haunts as well as friends and relatives I had not seen in decades. I dedicated that book to my parents, whose faith in the idea of creating a family out of their personal differences (my mother was English), in a country seeking to assert its own complex identity, has always been a source of inspiration to me.

In the absence of a clear direction, the country floundered, flopping left and right across the political spectrum. When it became clear that neither East nor West really offered a political model that worked, the ruling classes turned back towards Islam, hoping that this would offer a solution. It didn’t. Instead it increased the polarity and social division. Rather than solving the country’s problems, it created real anger and resentment. It was, in itself, a sign of the failure of the imagination.

In a Fractured State

When independence was declared in 1956, Sudan was an unknown quantity. The first generation of politicians, academics, and administrators were harvested from a narrow band of the social elite, primarily from the northern riverain tribes. The challenge facing them was enormous. They were despatched to Britain for higher education, with the hope that this would ensure their loyalty, allowing the old colonial power to retain some degree of influence. They learned how to wear suits and ties, to drink whisky and play tennis. They did not learn much about their fellow citizens.

Aside from the challenges facing the new nation, such as infrastructure and institutional needs, developing healthcare and education, there were also outside forces vying for influence. The Cold War pitched East and West against one another. A similar pattern could be seen across the continent. In Uganda, Milton Obote was overthrown and replaced by Idi Amin. In the Congo, Patrice Lumumba was murdered to allow Mobutu to step in. Sudan witnessed its own series of military coups which curtailed civilian rule. Army officers, trained in Britain and America, took it upon themselves to seize power, usually with disasterous results. In the continuous cycle from military to civilian rule and back again, lay the gradual decline of secular political evolution and the discourse of civil society. Corruption and incompetence gave rise to cynicism. The peripheral regions were increasingly ignored, their voices silenced. The inability to cope with natural disasters, such as drought and famine, gave rise to a steady exodus towards the capital. The civil war in the south being reignited in 1983 with the discovery of oil produced more greed, corruption, and incompetence.

By the time of the revolution in 2019, the political landscape had become a barren space with little room for any kind of dissent or possibility of change. The revolution that brought down Bashir in 2019 unleashed a complex struggle for political equilibrium. Popular support for a progressive form of civilian rule was hindered by infighting and division. Younger, more impatient activists clashed with older ones who had spent decades in prison or in exile, accumulating bitterness and frustration. At the same time, counter-revolutionary forces were actively seeking to prevent change. Remnants of the old regime clung to power, with support from external actors like Egypt, the UAE, and the conservative forces of Saudi Arabia. Perched atop this tottering pyre were the armed forces, who had built themselves a lucrative nest across three decades of Bashir’s rule. In October 2021, the two generals lost patience with the ongoing transition and, in the country’s long tradition of military interventions, staged a coup d’état that ended the transfer of power to a civilian government. The unstable alliance lasted until April 2023 when Hemedti refused to bring his RSF under the control of the national army and war was unleashed on the nation.

Younger, more impatient activists clashed with older ones who had spent decades in prison or in exile, accumulating bitterness and frustration.

It is easy to see how Hemedti, or Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, to give him his full name, might have convinced himself that he was blessed by the powers that be. In 2014, the EU invested 4.5 billion euros in a scheme to halt migration from the Horn of Africa. A hefty chunk of this was funnelled to Hemedti and his fighters, despite their record as a genocidal militia. This deal, effectively making them Europe’s border patrol, legitimised the RSF in the eyes of Hemedti and his followers. He had risen from being an illiterate camel herder running marauding gangs of Janjaweed raiders in Darfur to being one of Bashir’s most trusted officers. His men had fought in Yemen on behalf of the UAE and he had accumulated a personal fortune worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The brutality of the RSF can be understood as a form of retribution: the revenge of those who feel they have long been marginalised, ostracised, ignored, and exploited. The violence meted out to break up the civilian protest camps in June 2019 by the RSF and the forces of the Transitional Military Council was unprecedented, at least in the capital. A hundred and twenty-eight people were killed, over seventy rapes were reported. Bodies were thrown into the river. Where did such vehemence come from? While there is a case to be made for the neglect, corruption and indifference of the ruling classes towards those living in the remote provinces, surely nothing justifies the violence inflicted by the RSF both in Khartoum and elsewhere. The millions displaced, the hundreds of thousands who have been killed and who are still to be killed. Murder, torture, and rape. Political grievances demand political action, not violence. Somehow that message has been lost.

Hemedti himself clearly shares this resentment. He declared that he would reduce Khartoum to a place fit only for cats—another surreal echo of the city’s past. In 1885, Khartoum was razed to the ground by the Mahdi’s devotees. It was abandoned for over a decade. The statement reveals a lot about his motives, and his lack of interest in actually ruling the country. On the other side is Burhan, a mediocre military officer and a clear product of the Bashir regime’s incompetence. It has become clear that neither man really has a plan for the country. Neither has shown a particular interest in the welfare or future of Sudan. They are interested in what they can get out of it personally and the hell with the consequences. This is a re-run of the same military arrogance that has ruled the country, and indeed the region, for centuries.

The New Imperialism

Sudan’s natural resources have long exerted a fascination on the world, beginning with the Nile. For centuries its source was shrouded in the “mysteries” of the African continent. Ptolemy mapped its source to the Mountains of the Moon—Kilimanjaro. Eratosthenes traced the curve of the river through Nubia, and the geographer Strabo continued this fascination. Herodotus, the “Father of History,” described the enigmatic “island” of Meroë, capital of the Kingdom of Kush and the fabled Table of the Sun which was said to be laden with food that was replenished every night. In the European imagination, Sudan, like the rest of Africa, was lost in the foggy depths of myth. In some ways this has changed little.

In the European imagination, Sudan, like the rest of Africa, was lost in the foggy depths of myth. In some ways this has changed little.

One could argue that all of the newly independent nations of Africa, so vividly celebrated in the 1960s, were set up to fail. The colonial powers divided the continent up between them to serve their own interests, with scant regard for ethnic or religious divides, and ignorant of the history that preceded their arrival. Europeans were interested in what worked for Europe. Independence simply meant business as usual, but without the political responsibility for people and country. When this wasn’t forthcoming, political assassinations and coups would follow to replace uncooperative leaders with more willing partners. Looking at the mayhem that currently reigns across the Sahel today it’s hard not to see this chaos as the logical outcome of the short-sighted and self-serving policies that have been in place for seventy years or more.

Now it seems a new age of imperialism is upon us. This time the great powers vying for influence in the region are Russia and the UAE, along with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, and China. European influence has stagnated, trapped in mothballed colonial tropes. The new players are happy to stoke the war machine regardless of the human consequences, so long as it gives them what they need. Russia wants gold and minerals to fund its war in Ukraine, along with the chance to establish a foothold on the Red Sea, something China would also like. The Emiratis are investing billions to access fertile soil and water for huge agricultural projects, along with a modern port, free trade zone and an airport north of Port Sudan. The UAE also benefits from the gold passing through Dubai’s markets. In return, they provide money and weapons to the RSF. Egypt seeks security, meaning military rule rather than democracy, and no Islamists. They want control over the Nile waters, their lifeblood.

We have regressed to a medieval age of famine and suffering at the hands of warlords and mercenaries. According to a Reuters news report the famine affecting people is so bad it is forcing them to eat dirt and leaves. I am reminded of the soldiers in Gordon Pasha’s garrison in Khartoum, beseiged by the Mahdi’s followers in 1883. Reports at the time spoke of the soldiers boiling the leather bindings on their beds to make soup.

The ripples extend outwards from Khartoum, to Darfur and beyond, in a fault line that snakes across the Sahel, through Eritrea, Chad, Congo, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali, and Libya. Arms and fighters flow freely from one lawless state to another. There is no shortage of weapons or backers to fuel conflict, whereas supporters of peace, of civilian rule, and of common sense are scattered and powerless. The world looks on in silence, their compassion exhausted by conflicts in Gaza, Lebanon and of course, Ukraine. Has anything really changed since the dark days of the nineteenth century? The lack of media interest is possibly explained by the fact that Sudan occupies a blindspot on the map. It’s still shrouded in the foggy allure of the dark continent. A place so far below the radar of the average observer that wanton destruction, rape, mass murder, and genocide can pass without notice. In today’s brave new world of drone warfare and artificial intelligence, when fake social media accounts are used to sow even more confusion, we have entered a maze of mirrors where the very principles we claim to embrace have been abandoned.

The Inheritance of Loss

The first time I visited Nubia was in the winter of 1989. This was before Osama Bin Laden’s money had built the tarmac road to the North. In those days there was nothing but a dirt track in the sand. We drove in an old government Toyota Land Cruiser that rattled and shook as we bumped our way through the ruts. It felt like an adventure. With no roads or filling stations, we carried all the fuel we needed in a petrol drum that was bolted onto the back of the car. Nothing to see but open space for five hours. Flat ground dotted by huge boulders of granite and dazzling quartzite. We stopped for boiled eggs and coffee flavoured with ginger at a rakuba covered by dusty palm fronds. In the distance we glimpsed a white dome or qubba belonging to a local saint, suggesting that somehow we had dropped off the grid and were venturing into mystical terrain.

The following morning we visited the northern pyramid complex at Meroë and I saw for the first time the strange, broken-tooth tombs, the oldest of which date back to around 750 BC. The pointed apexes were blasted off with dynamite by an Italian adventurer named Giuseppe Fer-lini in 1835. Adventurer is a generous term for a man whose only aim was to enrich himself. Ferlini travelled to Nubia with the permission of the Khedive Ali Pasha, whose main interest in Sudan was finding gold and slaves. At some point Ferlini deserted and went in search of treasure, convinced that the pyramids were filled with gold. By all accounts, he found enough valuable objects to allow him to live out his days in comfort. In the process he destroyed some forty pyramids, leaving many of them with their distinctive shattered tooth shape.

For around five centuries, up until around 1000 BC, Nubia, or Kush as it was known then, was occupied by Egyptian garrisons, whose fortresses can still be seen today. When they departed, they left behind a cultural heritage that grew more distinct, with its own local deities such as Apademac, and a matriarchal system embodied in the figure of Queen Kandaka. When Alexander the Great invaded Egypt in the 4th century BC, Kush began to draw the interest of the Classical world. The Greek geographer Strabo travelled through Egypt and described the problems the Romans had with the one-eyed Queen Kandaka and her “Aethiopians,” as they referred to the Nubians, meaning the “burnt faces.”

This cultural heritage is now being plundered, with reports of trucks filled with priceless artefacts being driven away from the National Museum. The removal of national history is the ultimate form of erasure. The statues of ancient kings and queens, the delicate frescoes telling the story of four centuries of Christian rule in the north are now on sale on the dark web.

And if the past has been stolen there is also no guarantee of a future. After two years of fighting we have reached a stalemate. Neither Hemedti nor Burhan seems fit to rule the country, even if they wanted to. Maintaining the current status quo is their best option—settling into an uneasy coexistence while they continue to profit from looting, from the hundreds of tonnes of gold being exported and from the weapons and logistical support of external powers which are paying to protect their interests.

We have become a world in which endless wars are fought by forces concerned not with democracy, or the rule of law, not with justice, or even humanity, but with their own narrow interests. The West’s rhetoric of morality and social justice, of spreading democracy, appears increasingly hollow in the face of so many conflicts ignored. In Sudan, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and of course Gaza, the West appears to be most concerned with saving face and protecting their economic interests. The outside players have no interest in shutting down their proxies. Indeed, the whole concept of democracy now appears to be an absurd charade.

The West’s rhetoric of morality and social justice, of spreading democracy, appears increasingly hollow in the face of so many conflicts ignored.

There are reports of mass killings in Gezira, where men were rounded up, humiliated, tortured and executed by the RSF. In Darfur, a hundred and thirty women drowned themselves in a mass suicide to avoid being raped. An estimated ten million people have been displaced, losing their homes, their families and their welfare. Yet the world remains largely silent. On the sliding scale of global disasters Sudan comes in last, behind the horrors of Gaza and Ukraine.

The SAF’s latest advances, in Omdurman and Wad Medani, might be cause for cautious optimism. Images of people in Omdurman going about their lives again and of celebrations in liberated Wad Medani are certainly welcome, but they do not spell the end of the crisis. The RSF is far from defeated and is unlikely to cede more valuable territory, especially in Darfur, where the latest drone attack on a hospital in El Fasher shows just how ruthless and cruel they can be. All this, despite their ongoing campaign of widespread rape and murder having been finally recognized as genocide by the outgoing US administration.

To bear witness is to recognise our collective failure. When I see the horrific images of Gaza, the dead children shivering in horror, having lost limbs, all their family members, their homes, I feel the same. To them this world must seem like an incomprehensible nightmare. We have all, collectively, failed them, just as we have failed the people of Sudan.

People talk about being in shock. How could this happen? Such a comprehensive breakdown of law and order, the complete collapse of what was a functioning nation? And yet the signs have been there for decades, in the steadily encroaching madness, failures of governance and lack of accountability dating back through the eighties and even earlier, perhaps as far as Nimeiri, who gradually succumbed to the paranoia and supersition of a man who has lost all bearings, replacing technocrats with soothsayers and religious advisors. There is no small irony in this; looking back from the lawlessness and madness that now rules what remains of the country. If peace were to come tomorrow it would still take decades of suffering, pain and hard work to restore the country to some semblance of its former self, but some things cannot be recovered. Whatever the future brings, the country will be irrevocably different from what was before: nothing will ever be the same again.