by Bénédicte Boisseron

When my brother Luc Junior was two years old, dad took him along with mom to Guadeloupe for a visit. It was the late sixties, I wasn’t born yet, neither was my sister Sophie. Dad wanted to introduce his native island to mom, and he also carried the hope that Junior would connect with his roots at an early age. Dad was quite detached from his culture in his daily life in France, he didn’t even speak Creole at home, so it was never too early for Junior to start bonding with the island. In a picture I recently found in the family album, you can see dad in a dark pair of trunks walking down the beach showing off his toned body. With a large smile on his face, he is holding Junior by the hand while walking towards mom who is immortalizing the moment behind the lens. In another picture, dad is sitting on a chair and holding, with one hand, a coconut fruit cut at the top in the shape of a bowl. Mom is standing behind him smiling down at him while Junior is standing in front of him, visibly eager to grab the fruit. The three look like the perfect family.

I don’t know if connecting with one’s roots follows the same rules as taking up a sport or learning a language, namely the sooner one starts the better one will be at it, but I was already twenty-seven and my sister Sophie thirty years old when the two of us went to Guadeloupe for the first time. We had been kept out of touch with our Caribbean roots, and it showed. Landing in the Pointe-à-Pitre airport felt nothing like a homecoming—Sophie and I looked like random tourists. Junior, on the other hand, reconnected with the French Antilles much sooner. In his late teens, he had found a way through an internship to spend the summer in the French Caribbean Island of Martinique, Guadeloupe’s sister island. At the end of the summer, as he headed back to the mainland, he vowed one day to move permanently to one of the two islands. My brother was the real deal. He had always had this Caribbean je-ne-sais-quoi that would eventually morph into a pressing need for an Aliyah, a spiritual move back to the roots.

Once Junior moved permanently to Guadeloupe, he took this calling very seriously. He went back to basics and embraced everything that didn’t scream French, western, and White. Junior knew that the traditional Afro-Caribbean population preferred rivers over the ocean, so he claimed not to care much for beaches. He discovered the unique pleasure of soaking his lean brown body in the icy cold water of rivers nearby, flipping his drenched dreads away from his face as the water dripped down his face. My brother made sure that locals didn’t mistake him for one of those Guadeloupeans who had spent too much time in the French mainland, the “metropole.” He didn’t want to come across as a Europeanized Guadeloupean, what they call mockingly in Guadeloupe a “négropolitain.” Though none of us grew up speaking dad’s native language, Junior was catching on fast with French Creole, throwing a Creole word here and there in the conversation. In Guadeloupe, my brother rented a small house where papayas, passion fruit, and guava grew in the backyard; those were fruits he had never heard of growing up in the Parisian suburb. He also made sure to buy mostly fresh produce straight out of the nearby fields from street vendors, as he loudly rejected supermarkets that offered overpriced French imports and processed food. As a culmination of his new lifestyle, he started adding roots to his diet. He learned how to cook ignames, malangas, madères, and poyos, traditional vegetable roots eaten by our ancestors. I marveled at his transformation and commitment. He was geographically, spiritually, and gastronomically Black to the roots.

I marveled at his transformation and commitment. He was geographically, spiritually, and gastronomically Black to the roots.

Junior was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer in 2006. The news came out of nowhere. He was only thirty-nine years old and about to be a father. In 2007, a year after his diagnosis, a book came out entitled Chronicle of an Announced Poisoning. It was the first time that the general public would hear about an environmental crisis of epic proportion in the French Antilles. The whistleblowers, Martinican author Raphaël Confiant and ecologist Louis Boutrin, were telling us that the soil of Martinique and Guadeloupe had been poisoned. The population would have to avoid consuming local products growing in direct contact with the soil at all costs. Roots, as it were, could kill you.

******

My brother’s dream was to live off-the-grid, the French grid that is. Off-the-grid, in the most basic terms, means off the electrical grid but there are so many kinds of grids. Living off-the-grid requires finding one’s own power away from power stations, living somewhere outside the system. Junior’s off-the-grid was modeled after the maroon, what the French Creole calls nèg maron. The maroon was the slave who ran away from the plantation, not to the north, like in the American history of fugitive slaves, but into the wilderness. In the French Caribbean history, there are no such figures as Frederick Douglass or Harriet Jacobs. The idea of a literate slave escaping slavery by going up north and joining the abolitionist intelligentsia is not technically feasible on an island. Surrounded on all sides by water, there is no land to escape to. In the Caribbean, being a fugitive means going off-the-grid into the wilderness, what is called “marooning.” Fugitive slaves would hide in the woods and create their own settlement far from the plantation. To sustain themselves, they would work the land, hunt, and even sneak back onto the plantation at night to steal provisions. To some respect, maroons were the original Black freegans, they sustained themselves outside the system, away from the plantational grid, grabbing things as they came, and rejecting being fed by the hand that enslaved them. And when they stole food at night from the plantation, they just took back what was owed to them.

In Guadeloupe, the most iconic maroon was a mulatto woman nicknamed La Mulâtresse Solitude, a legendary figure from the early 1800s who had lived on a maroon settlement in the woods and joined armed forces against the French troops when Napoleon tried to reinstate slavery on the island. Slavery was abolished in the French Caribbean islands in 1794, and Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated it in 1802. As we know, his attempts to reinstate slavery failed in Saint-Domingue where the resistance broke into a revolution that culminated into Saint-Domingue gaining its independence and becoming Haiti, the first Black Republic. In Guadeloupe and Martinique, however, the formerly enslaved insurgents were not so successful, the French troops crushed their resistance. As an active participant in the armed resistance, Solitude, then a few months pregnant, was captured and condemned to death by the French, but not before she gave birth to her child who, per the reinstated law, would be born into slavery. Her execution was delayed by six months to allow time for gestation, she was hung the day after giving birth. The story of La Mulâtresse Solitude was immortalized by French novelist André Schwarz-Bart in a 1972 novel of the same name. Solitude is traditionally represented as pregnant and striking a defiant pose. There is a statue of Solitude in Les Abymes in Guadeloupe. It is located at the center of a roundabout so that drivers can look at her from all sides. In 2022, the French government erected a statue in her honor in Paris, where she is also shown as pregnant and holding the proclamation of Louis Delgrès, a rallying cry of resistance against Bonaparte troops by its leader. The Mulâtresse Solitude statue is the first statue of a Black woman erected in Paris. Solitude embodies the revolutionary side of going off-the-grid. Her pregnancy is the promise of future generations taking over her mission by taking on the woods.

Even though today Guadeloupe is part of France, the fight continues. Junior carried the legacy of Solitude; he was intent on going off the French grid. My brother understood the importance of detoxification from the French culture. He believed in self-reliance and eating local, down to the roots. What he had not planned for, however, is the extent of France’s poisonous reach. France has a way of forcing insurgents into the open.

There are no poisonous snakes in Guadeloupe, the poison on the island comes from somewhere else. I remember asking dad why there were no venomous snakes in Guadeloupe while there were some in Martinique. I had a hard time understanding this difference since the two islands are like siblings with a shared history and topography. I was always amazed at the fact that there are no animal species threatening human life in Guadeloupe, nothing that could deter a person from venturing into the wilderness. Dad had an explanation for it. According to him, defiant slaves in Guadeloupe never gave the colonials a chance to introduce a species that would deter slaves from running away into the woods. This explanation reflected what I had heard in the past from an older generation in Guadeloupe. No one messes with Guadeloupeans. As some people had told me before, unlike Martinicans, Guadeloupeans have revolutionary blood running through their veins. The reason is that during the French Revolution, Martinique fell under British occupation so that royalist planters could maintain slavery, while Guadeloupe was able to fend off the occupation and maintain the abolition of slavery under the French revolutionary regime. Unlike Martinique, Guadeloupe experienced the French Terror, a guillotine was even brought to the island to execute anti-revolutionaries. Dad’s answer to my question about snakes is typical of this image of a fierce and revolutionary predisposition endemic to Guadeloupe. No one would have ever dared bring venomous snakes to the island. But according to dad, the colonials introduced a poisonous viper called fer-de-lance onto Martinique to make it more challenging for would-be maroons to live in the wild. During the era of slavery, the viper was Martinique’s Achilles-heel.

Dad always had a whimsical imagination. His story was part of a mythology fueled by a long-standing sibling rivalry between Martinique and Guadeloupe. In his mind, Guadeloupe had a revolutionary ecology that set it apart from other islands, and particularly from Martinique. But the truth is that the French colonials were not responsible for the presence of the viper in Martinique, the poisonous snake actually predates the colonial era. Already back in the 1600s, French author Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre had mentioned a poisonous snake infestation in Martinique that allegedly hindered settlement efforts. Du Tertre, in his historical account of native populations in the French Antilles, posits that the native tribe Arawaks may have introduced the fer-de-lance to Martinique as a biological warfare against their sworn enemies, the Caribs. Granted, Du Tertre’s version is not that different from my dad’s, both point to the poisonous snake in Martinique as the result of biological warfare, but let’s give credit where credit is due, the colonials did not introduce the venom in Martinique, even though they certainly used its presence against recalcitrant slaves to their advantage.

Today, the possibility of running into a venomous snake in Martinique makes hikers a bit more cautious as they set foot into the woods. In Guadeloupe, on the other hand, my brother’s foot was as carefree as could be. In his neck of the woods, there was nothing to fear. He didn’t know that a poison seeping into the soil of his island could be more deadly than any fer de lances.

******

Chlordecone (called kepone in English) started being produced in America in the fifties. Its use in food crops was soon deemed hazardous and the chemical was quickly banned in the agriculture sector in America. Less than one percent of its production remained in use in America for the purpose of cockroach and ant traps while the remaining production was meant for exports. In the early seventies, due to the production of the chemical, an ecological crisis erupted in Hopewell, Virginia, when the company dumped the wastewater from production into the sewage system leading to the James River. Due to exposure, workers from the plant and the immediate community started exhibiting signs of illness, which prompted the Health Department to close the plant and start a plan to monitor the quality of the water from the James River. Traces of kepone are still traceable today in the water samples, which shows the persistent nature of the chemical.

America was quick to react to what was immediately acknowledged as an environmental disaster. France, on the other hand, wouldn’t be so quick. Even though the Hopewell scandal had been well-publicized, banana planters in Martinique and Guadeloupe would be given carte blanche to use chlordecone in their fields. Banana plantations being the main cash crops on the two islands, saving the bananas was crucial to the economy of the islands. Between 1972 and 1993, chlordecone was massively sprayed on banana plants to fight a weevil invasion on banana plantations. As early as the late sixties, France had taken note of the dangers of chlordecone, but the country let the poison infiltrate the soil of its overseas departments with impunity. With rainwater, chlordecone would slowly spread, gradually reaching people’s gardens, finding its way into the rivers and the ocean, contaminating the fish as well as the vegetables and the livestock. Finally in 1990, the French Agriculture Department declared chlordecone a health hazard and banned its use, only for the planters to persuade the French government to give them a three-year extension that would allow them to clear their stocks. At the planters’ request and with France’s permission, for the next three years a pesticide now officially declared a health hazard would keep being poured into the soil of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

At the planters’ request and with France’s permission, for the next three years a pesticide now officially declared a health hazard would keep being poured into the soil of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

The chlordecone scandal, nicknamed “the new Chernobyl,” was (and is) not only an ecological crisis, it was (and is) also a colonial one. Most of the planters in the French Antilles are békés, which is the name for the descendants of White planters from the slavery era. After the abolition of slavery, the white planters got indemnified by the French government for the loss of their slaves. History repeating itself, now békés were granted a special permission to prioritize their assets (their stocks) over the lives of the local population. Scientists predict that chlordecone will remain in the soil of the French Antilles for the next seven hundred years. Recent studies have identified a connection between certain cancers and chlordecone contamination. Guadeloupe and Martinique, for example, have the largest rate of prostate cancer in the world. In 2006, when my brother was diagnosed with cancer, most of the population had never heard of chlordecone but they all had it running in their blood. Ninety-three percent of the population in Guadeloupe and ninety-five in Martinique allegedly have traces of chlordecone in their blood. I’m not saying that my brother’s colon was poisoned by the venomous roots he ate, there is no scientific proof to it, but science is only one side of the story. Like dad, I rely on mythology to hear the other side. I just know that when my brother flew back to France to get treated for his cancer, I had a vision of Solitude hiding behind trees, wiping off tears as she looked up into the sky and saw the plane disappear into the clouds.

Sadness, despair, resilience, and defiance, those were the successive steps following the news of the cancer diagnosis. We were hoping for remission and the return to a semblance of normalcy. Remission did come, but not normalcy. Instead, dysfunctionality took over. My brother cut ties with all of us and never talked to us again. My sister in France, my parents in Guadeloupe, me in America—we stood in different parts of the world with my brother’s resounding silence between us. We never saw him again, except for dad who was shown a video of his dying son taken at the hospice. A few days before his death, my brother had recorded himself talking to his nine-year-old son. It is uncanny to think of dad looking at his son’s face on an iPhone as his son in the video lay dying next to his own son.

—How did he look?” I asked dad.

—His dreads were gone,” he said, not wanting to say more—he didn’t need to.

******

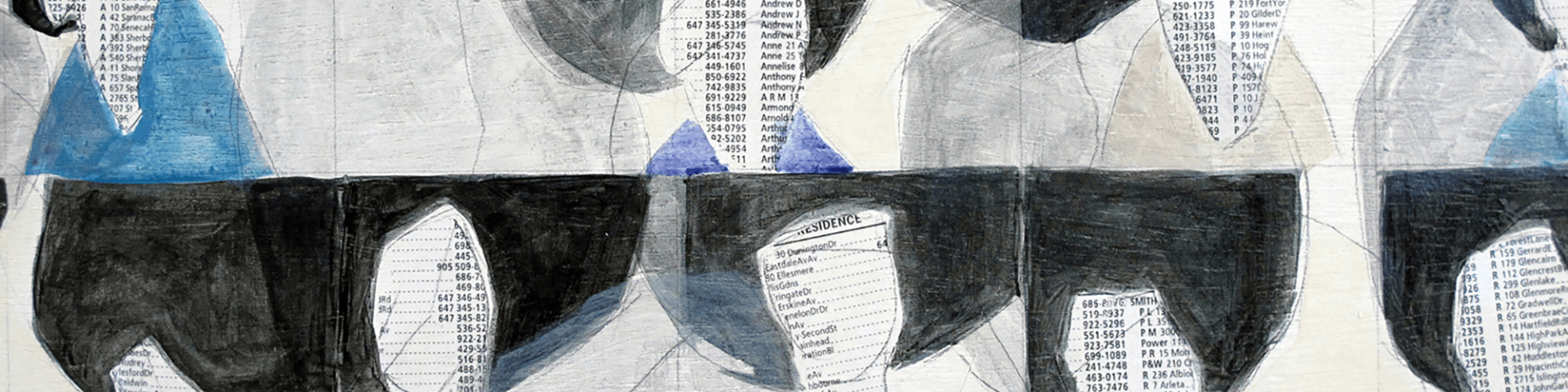

Junior had beautiful black and curly hair, which he kept relatively short until he was sixteen, at which point his hairstyle changed due to his love for tennis. Not that he played tennis, my brother didn’t play any sports, but his living icon was a tennis player known for his unique hairstyle. In 1983, Yannick Noah, born of a father from Cameroon and a French mother, was a newcomer in the world of tennis. To everyone’s surprise, the unknown biracial young man had made it to the final of the French Open. The twenty-three-year-old was clearly the underdog against Swedish Mats Wilander. France had not won the French Open since 1946. But on June 5th, Noah won the final. France was bursting with pride, even those who were not fans of tennis. At home, we had almost missed the historical moment. It was an unusually warm late Spring Day in the Parisian region, and my parents were having their annual backyard lunch party, not aware that it would conflict with the final. On the morning of the final, my parents started receiving phone calls from friends concerned about missing the game. My parents had to think on their feet. They brought the heavy television set into the backyard and connected it somehow to the antenna and to an outlet with an extension cord running through the living room window. The bulky set stood incongruously on a table underneath the lilac bushes, the shade providing a clearer image on the screen. I had never heard of an outdoor television; it was a genius idea. Once the crucial match point arrived, our eyes were riveted to the screen. Wilander’s ball is out, Noah falls to his knees, raises his hands in the air, and lets out a cry of joy. He then gets up, quickly shakes his opponent’s hand while jumping through the net to run into his dad’s arms in the most touching embrace ever seen between a father and a son. My parents’ guests were cheering loudly, puffing on their cigarettes, and sipping their wine ecstatically. For the French, it was as magic as the moment when Obama was elected for the first time. Together, we were rooting and cheering for an unprecedented, brown-skinned French champion. “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” is a quotation artist Glen Ligon borrows from Zora Neale Hurston for his 1992 print, which poet Claudia Rankine then uses to depict Serena Williams’ exacerbated Blackness within the white world of tennis. Yannick Noah was the French Serena Williams of the 80s. He didn’t back down against the White background. Not only was he half-African, but he was also defiant enough to wear African braids on the tennis court, which was a first. His play was energetic and theatrical, and his braids moved with every stroke of the ball.

Junior wanted to look just like Noah, but mom was not the kind of mom to bring her son to a professional hairdresser in Chateau-Rouge, the African neighborhood in Paris. She decided to do it herself. After her workday in Paris, before catching her train home, mom would stop by an arts and crafts store to buy black knitting wool yarn for my brother. On Wednesday afternoon, her weekly afternoon off, she would sit in front of the television with Junior sitting on a chair placed between her legs and she would begin braiding her son’s hair with pieces of wool. It would take an average of five hours to complete the job, which ended with sore fingers and late dinner, but the job was done. One month later, son and mother would sit again in the same positions, this time to undo the work, let the hair breathe for two days and do it all over again. It was all worth it.

Many people didn’t know what to make of Noah’s wooly braids, they actually called them dreadlocks. Only later in life would Noah actually wear dreads, using his real hair for this style. Like Noah, Junior transitioned from braids to dreadlocks over the years, with various hairstyles in between. By his mid-thirties, he had a beautiful set of long dreadlocks. Dad never approved of his hairstyles, neither the braids, nor the dreadlocks. He was privy to what happens to a Black man who does not conform to French standards. Even in Guadeloupe, dreadlocks can be frowned upon because of their connection to Rastafarianism. Junior was never defiant when it came to dad, he always chose to retreat instead of face Goliath, but his hair told a different story.He secretly wished he could have crushed dad under the weight of his dreadlocks, leaving him dead on the side of the road, as he carried on alone the Luc Boisseron name. There had never been a Noah family-like embrace between dad and son in my family. There wouldn’t be one now that my brother lay dying in Paris. It’s not always a good idea to give your son your own name; father and son will battle it out over who can carry the name best. The two have always been in a tug of war, with dad in the lead. In the natural course of life, my brother would have been the one closing dad’s casket, relieved to be the only Luc Boisseron left. But things don’t always go as they should. Junior still had so much to prove, so many battles to fight. Dad’s four words “his dreads were gone” and the mental picture of my brother’s dreads falling off his head haunt me. Samson’s hair would not grow back, it was the end.

The image of Junior flipping his drenched dreads back in a thrusting head motion came back to me as I heard that he lay dying. This visual memory in my head turned into a tree violently tossed around in the path of a hurricane. His glistening body was the trunk, and the dreads were the branches. If everything had gone my brother’s way, he would have grown roots in the icy river, deep in the woods, but he would have needed more time for that. It takes time to grow roots. “It looks like a chokeberry tree,” the white girl said when she saw the badly scarred back of Sethe, the runaway slave in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Sethe had fled from the southern Sweet Home plantation to Ohio. Sweet Home is such a sweet name for a slave plantation; the name mirrors the beautiful trees bordering the path to the plantation house, trees strong enough to sustain the weight of a slave hung on a branch. From afar, centuries-old trees on southern slave plantations look so sweet, but from up close you can see that those branches stand for the scars of the overseer’s lashes. In Morrison’s story, the chokeberry tree looked beautiful at first, until it turned monstruous as Paul D saw the true nature of the tree pattern. Paul D got close to Sethe’s back to feel the tree. “He rubbed his cheek on her back and learned that way her sorrow, the roots of it; its wide trunk and intricate branches.” Someone should have done what Paul D did to (and for) Sethe. They should have tried to feel the extent of my brother’s sorrow, the roots of it, touching the wide trunk and intricate branches of his chemo drenched dreads before they fell off with the force of the westward wind coming from France.

I lost touch with Junior before the end. I never got to see the tree wither. We never had that conversation. I don’t know how it is to be in touch with your roots. I fear roots. Where my brother comes from, roots are deadly.

I don’t know how it is to be in touch with your roots. I fear roots. Where my brother comes from, roots are deadly.

******

In 1873, Frederick Douglass was invited to Nashville, Tennessee, to deliver an address in front of a newly emancipated audience. After emancipation, the formerly enslaved did not want to work the land. Agricultural work reminded them of forced labor and their formerly enslaved condition. Instead, many were migrating to the city. Douglass came to curb the exodus, hoping to convince some to stay and work the land. As Douglass said, “The very soil of your State was cursed with a burning sense of injustice. […] Thus you will see that emancipation has liberated the land as well as the people.” But what if Douglass had been wrong? What if the land of the formerly enslaved was forever cursed? What if leaders, descending from a long line of leaders and planters, knew how to make sure that the formerly enslaved would not find salvation in the land? Today, the land is not only cursed, but also poisoned. When I moved to Michigan in the midst of the Flint water crisis, I could not help but think of the Hopewell scandal, except that this time it was not the James River but the Flint River that had been contaminated with wastewater from chemical plants, and except that this time governmental officials were not so quick to action, they were actually complicit. And as I got inspired by Detroit urban farm movements reminiscent of the maroon tradition, I was dismayed to hear that the air and the soil of the predominantly Black city had become a health hazard due to toxic waste from private companies. As Detroit Metro Times wrote in 2020, “gone are the fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Residents no longer grow produce because the air and ground are contaminated with hazardous substances.” In other words, from north to south, living off-the-grid had become poisonous in the land of Blackness.

Junior very much enjoyed growing his own pineapples in Guadeloupe. Right after his diagnosis, before the family fallout, I flew to Guadeloupe to spend the summer in his house while he received treatment in Paris. He would often ask me on the phone about his pineapples as one enquires about children left behind. Are they growing? Did you water them? One day, I told him that one of them was ripe and that I ate it. It was my first time eating a pineapple straight out of a garden, it was exciting. Junior had a mixed reaction to the news. He seemed happy for me, but I could tell that he felt that the fruit should have been saved for him. It took two years to grow that pineapple. Why should I have been the one blessed with the timeliness of ripeness? I shouldn’t have profited from the land that I had never worked. So much patience, nurturing, and work for a land yielding its fruit to the undeserving one. The land was now out of touch with Junior, even though it was a land supposed to have sustained the maroons in their fight for freedom. The land should have been more accommodating to those who came to grow roots. I was like the prodigal son for whom God killed the fattened calf as he returned from a selfish life abroad while the older son did not get the honor of the fattened calf even though he is the one who stayed home to feed it. Maybe at the end of his life my brother felt that indeed the land was cursed. He probably felt that this land should have cursed me instead. As he came back from Paris on a wheelchair, looking ghastly, as someone who had just looked death straight in the eyes, I opened the gate of his home to greet him. Not long after, it was he who did the cursing. I had not kept the house to his standards, I had not rescued the plants from the unprecedented drought, I had become an unwelcome guest. That cursing would be the last time I heard his voice.

My brother passed away in August 2015. The news from Paris reached me on my way back to America after a conference trip in Mexico. Right after the news, I went to the doctor with sudden health issues and was scheduled for a colonoscopy. Was it the pineapple? It turned out nothing was wrong with me. I didn’t have colon cancer. What I had was survivor’s guilt. I felt a certain self-recrimination for not having Junior’s determination to find my roots. As people in Guadeloupe grew aware of the chlordecone contamination, some of them started buying and eating differently, and I was one of them. On my subsequent visits to Guadeloupe, I learned to avoid the street vendors selling fresh produce straight out of the fields. I became wary of unlabeled local products, relying more on bottled water and French imports. I started shopping like a négropolitain. As I pushed my cart to the cashier with shame and self-disappointment, I could hear Junior’s voice behind me. He was cursing me.

How to live off-the-grid when history compulsively repeats itself, forcing maroons into surrender? I often wonder about Solitude’s legacy and the nine-year old boy next to his dad on the iPhone video. Who will take his hand and take him to the woods?

******

As a child I loved growing things, particularly things underground, I liked getting my hands dirty. I was around six years old when we first experimented with growing potatoes. My parents had just bought a thatched house formerly used as a cow shed in a Normandy village with the plan of turning it into a summer residence. The village consisted of a main road with a few farms and small houses surrounded by fields with grazing cows. The milk cows were Guernsey cows, white with brown spots typical of the Normandy region, Guernsey being a small British island off the Normandy coast. When we started spending our summers there, neighbors could not ignore the fact that the cattle were no longer the only brown spots on the landscape. My parents called the house “Snow White” in their usual tongue and cheek humor. The house did look like a fairy tale house made for dwarfs with its extremely low ceiling, rustic charm, and the huge fireplace with a hook hanging down from the chimney meant for a giant iron cast cooking pot. As for the plot of land, you couldn’t precisely call it a yard or a lawn, it didn’t have that feel. It was rather two agricultural fields put together. The lot was massive and unkempt.

My parents didn’t wait for the house to look or feel like one before starting to spend their summers there. In our first summer in Normandy, dad dug a ditch at a fair distance from the ‘house’ and told us it would be used as a septic system for the summer. To relieve ourselves, our parents gave us a big enamel coated chamber pot with a handle to carry it. We were told to pour some bleach water in it, close the lid after use, carry the load outside, dump the content into the ditch, and finally scoop some dirt on it. After a few weeks of this routine, we knew the smell and look of our feces better than any other parts of our bodies. Obviously, this scatological experience was not the highlight of my childhood, but oddly enough, it taught me something. Being responsible for our feces showed us the realness of what is left behind.

After this experience, when the time came for the potato harvest, digging into the Normandy soil was not new to us. But unlike human feces, potatoes have a generative power to them. Life underground is full of riches, and the soil felt like a good storing place for all essentials. Potato plants are perennials: even if the plant part dies, tubers will survive harsh weather and give out a new plant the following season. In the meantime, in their vegetative state, tubers store nutrients and deliver those stored nutrients to the new plant when the time is right. Tubers show the power of underground living. Like hoarders in bunkers, tubers store enough to last them through the tough times until they can get out again. Even though potato tubers are perennials, they are usually treated as annuals since the tubers are harvested for food on a yearly basis.

—“Don’t be so greedy, mes enfants. Leave some in,” mom said.

—“Why not get them all? They’re going to rot anyway,” Junior asked.

—“No, they won’t. They’re perennials. If you leave some, as a token of gratitude they may give you more next year.”

For mom, leaving some of the potatoes in the ground was a way to honor the perennial resilience of life. She needed to keep a part of things underground, the part that stores nutrients in preparation for better times. Her perennial philosophy, including her off-the-grid septic system, was not lost on us, it resurfaced in different ways in our adult lives. Mom’s relation to soil and resilience have dominated our lives and it is what ultimately compelled both my brother and me to leave France. Mom tried to show us the value of underground nurturance, but her wisdom could only go so far. We children had to do our part in figuring out what this wisdom meant for us respectively. With time, I came to understand that what brought me to America was not so different from what had brought Junior to Guadeloupe. We were both looking for a fertile soil to nurture what had been kept in a vegetative stage in our lives. For both of us, this search was related to the need to unearth our Blackness.

Moving to America taught me that Black consciousness is of the perennial kind, it can survive underground and will come forth when the time is right. My off-the-grid experience was different in America than it was for my brother in Guadeloupe. For me, it was not about the woods, or a Solitude kind of off-the-grid, it was more a question of an inward off-the-grid, my feet sinking into the ground. My model was Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison. Richard Wright’s short story, “The Man Who Lived Underground,” was first published in the forties but the novel version of it was posthumously released in 2021. As the title suggests, Wright’s protagonist lives underground and survives on food scraps. Racially profiled, tortured, and killed by the police for a murder he did not commit, Wright’s protagonist, Fred Daniels, bears witness to America’s long-standing police brutality against Blacks. With a 2021 release date, many felt that The Man Who Lived Underground spoke to the George Floyd era. But for me, Fred Daniels is a great deal more than a harbinger of Black Lives Matter. The release of the novel occurred at the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world had just experienced a lockdown and life lived on short supplies. In 2021, we had just started to feel familiar with the vegetative state of underground living and the need to rely on stored nutrients. Fred Daniels is the original underground man of our modern era, and during the pandemic he became somehow all of us, but what makes him different than any other underground recluse, including the original underground man from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 19th century classic Notes from Underground, is that he is an African American. Daniels brings something more to the underground experience. In an American context, the Black underground man is someone who historically sustained the foundation of the country through his forced labor; and because he stands at the very foundation, deep underground, he is the only one able to shake that very foundation. Off-the-grid in the American tradition means not depending on the system but still being connected to it in order to subvert it. Being off-the-grid means being underground storing one’s nutrients, cut off from the system of production and consumption above ground, but ready to strike when the time is right. Being off-the-grid is to be freegan, Fred Daniels being the original Black freegan.

My off-the-grid experience was different in America than it was for my brother in Guadeloupe. For me, it was not about the woods, or a Solitude kind of off-the-grid, it was more a question of an inward off-the-grid, my feet sinking into the ground. My model was Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison.

If Wright’s story sounds familiar, it is because Ellison envisioned a similar underground story in his 1952 novel, Invisible Man. Ellison’s book takes after Wright’s story. Ellison’s protagonist would rather live off the grid, without paying for consumption, living underground with stolen electricity, than be part of a rigged system that always put him last. Ellison’s underground man literally got his power from hacking the power company. The underground living space in the African American context has something of a perennial resilience, it is a special kind of off-the-grid which, instead of stepping away, subverts the system from within. In a 1945 article about Richard Wright’s memoir Black Boy, Ellison talked about Wright’s extraordinary achievement to convert “the American Negro impulse towards self-annihilation and ‘going-under-ground’ into a will to confront the world.” In the Black tradition, underground resistance is a way to retreat so as to better strike. The underground man can surface at any time out of the manholes of American history.

“This memory of growing things, anything, outside not inside, remained in my memory,” novelist Antiguan American author Jamaica Kincaid writes. Growing things is also something that remains in my memory. I understand the power of roots, of growing roots in any soil that makes sense to me. I also understand what the potatoes meant to mom and the pineapple to Junior. Mom and Junior were growers, they left their deepest joy and sorrow in the soil of their choice. Like them, I am learning about perennial resistance in the land of my choice, letting my roots grow in America, this new country of mine.