by Dagmawi Woubshet

From August 18 to September 18, 2023, a remarkable outdoor exhibition popped up on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Beyond Granite: Pulling Together featured six artists who, for a month, transformed the nation’s premier civic and memorial stage into a compelling site of art, critical inquiry, and commemoration. Dagmawi Woubshet spoke with Ashon T. Crawley, one of the six featured artists, whose mixed-media sound installation, HOMEGOING, offers a powerful exploration of the impact of the AIDS crisis and the legacy of Black queer church musicians gone too soon.

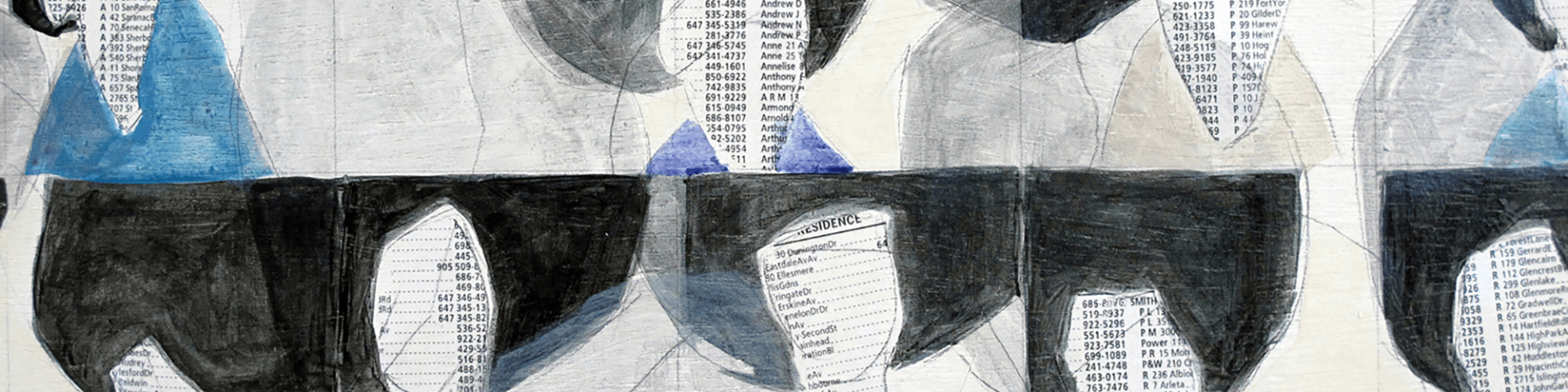

Dagmawi Woubshet: Ashon, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. As I said to you at the opening of the Beyond Granite: Pulling Together exhibition, I found your piece HOMEGOING to be so moving. It’s a brilliant audiovisual public installation and also a work imbued with a deep ethical commitment to commemorate the dead. I wonder if you can begin by describing the piece. It’s an installation with clear sonic and sculptural features. It’s also divided into three different sections: Procession, Sanctuary, and Benediction. Can you say more about how its design, including its tripartite structure, came to be.

What I was trying to do with these three different stages was to think, sort of along with Hortense Spillers, when she says that blackness is a vestibular culture.

Ashon Crowley: What I was trying to do with these three different stages was to think, sort of along with Hortense Spillers, when she says that blackness is a vestibular culture. I started thinking about vestibules a lot when I first read that—the place that is the place of waiting, the place of resting, the place of meeting. The vestibule in church was where we would wait to go inside of the sanctuary, but it was also the place where we would leave the sanctuary in the middle of the service if we wanted to talk to someone or if we needed to use the restroom. The vestibule was the sort of place that was a holding pattern for you to be able to recognize that there was something sacred happening just beyond you. And so I wanted a section of the piece to set the sacred occasion. The entire thing, as you know, is a sonic memorial. I wanted something, in terms of the physical manifestation of the installation, to announce that this is a sacred occasion, and I wanted to do so not only in the physical build platform, but also in how the sound would be heard. The first section is the two platforms, and the speakers are in the interior of the two platforms. They face each other, but they don’t face on the outside. The desire was for people to move within the interior space between the two platforms. Once you are in the middle of those two platforms, you really get a sense that there’s actually music playing. You hear that there is music playing if you’re standing on the street, on the sidewalk—that was purposeful—just to get people who are walking by the Mall to hear something. But you couldn’t hear the actual content of what was being played until you’re in the middle of, or in the interior of Procession. In Procession, there are the names of 305 people who died of AIDS complications. Those names are whispered mostly over the sounds of strings that composer and artist JJJJJerome Ellis provided, with me improvising on the Hammond organ on top of the strings. It’s a low, meditative, and very quiet fourteen-minute song. That intention and desire was to get people to recognize that this is a solemn and sacred occasion. These first and middle names are being offered in a way that still maintains an anonymity. It stresses the importance of recognizing that these are individual people, but there is a kind of ephemeral quality to the saying of the name. The desire for Procession was to usher people into the occasion, to recognize that it was something that you would need to slow down and pause to take fully in. This is my first public art piece or public installation. And I was told many times that people really speed through and don’t necessarily take the time to sit with things. It was a risk to create something with a fourteen-minute song, before a song that’s twenty minutes long, and then another song that’s twelve minutes long, because you’re asking people to really dedicate a long time. But I was very surprised every time that I went and sat back and watched. I was surprised at how many people actually just sat and listened to the entire first movement, and then they would move from Procession, and walk to Sanctuary. Sanctuary is the section that had four songs that I composed for a choir—I took two songs from three different musicians, so six songs in total, and I took the lyrics of those borrowed songs and dumped them into a unique word finder. Then I selected key words that resonated with me, that moved me—that I felt I could build a song around. So I wrote four songs using the key words from the songs of the musicians, singers, and choir directors who had died, and whom I was referencing and thinking about, and used their lyrical content as the basis for the lyrical content for the four songs that I composed. I also used the chord changes, progressions, and resolves that they would use commonly in their music as the basis for the four songs that I constructed. So, none of the songs are anything that they created, but each of the songs is in conversation, in a literal sonic conversation, with both the lyrical and sonic content that these musicians, singers, and choir directors would perform. The four songs are all sung to, and about, these particular people who are now deceased. They’re songs that are encouraging them to leave this plane of existence if they so desire, songs that celebrate the life of who they were, their contributions, but also recognize that it is time to rest if you would like to rest. It is time to go beyond glory, if you would like to go beyond glory. I don’t believe in Heaven. I don’t believe in Hell. And so, trying to announce that this is an occasion, a celebratory occasion, but an occasion to give and offer ceremony and homegoing, it felt necessary to sing directly to them. It’s important, too, that none of the songs are written to or about God. That’s intentional. This could also be seen as a critique of very specific God concepts, if a critique of the God concept itself, and trying to say that we can practice this kind of energetic force. We can practice this social music without God being the center and root of it while at the same time not degrading those who believe in God and wanting to be in a social relation with all kinds of people with all kinds of beliefs. The four songs were composed with these musicians in mind.

The physical manifestation of Sanctuary comes from the word’s roots in Arabic. The aerial shots made it much clearer. When people walked through it, they thought they were walking through a maze. (It does have a maze-like feel.) But what they were actually moving through was the word Amin, which means “Let this prayer be accepted.” It was constructed with Kufi Arabic scripting, which is a square scripting, or a very angular scripting that has the same amount of negative space as filled in space, and so each of the words are deeply balanced in terms of what was on the ground, both the grass and the actual installation piece offsetting each other. As people were moving through what felt like a maze, they were actually moving through prayer. They were moving through the prayer, “Let this prayer be accepted,” and they were also moving through the word, “Let this prayer be accepted.” I wanted to use this as the ground plan and the movement plan for a couple of different reasons. One is because proximity is something that musicians, singers, and choir directors, and people in general who were living with HIV and died of AIDS complications, were refused, often, when they were dying. People would refuse to touch them, refuse to shake hands, refuse to hug them, even within the context of church services, they were refused. One of the things I wanted for the installation was to compel proximity. You had to be close to what was happening to get a sense of what was being heard or what was being sung or what was being performed. When you’re in the middle of Procession, that’s when you most fully hear it. When you’re in the middle of Sanctuary, that’s when you most fully hear it, because no matter if you are standing, using a wheelchair, or, if a child, rolled in a stroller, you have to be in close proximity to really get a sense of the occasion. That was intentional. But I also wanted to mark the relationship between Black gospel music and Islam. I’ve been researching and writing about the relationship between the blues and gospel music, and the blues has its basis in Islamic prayer. I wanted a history that has been hidden but no less real, a history that has been forgotten perhaps, the history of Islam as a sonic basis for what’s happening in the Black Church. I was trying to do a similar kind of thing with the musicians, singers, and choir directors who died. Their sonic tradition is a foundation for a lot of what is heard, even still today in Black churches, and yet there is this hiddenness and this intentional forgetting of these his- tories. Trying to produce reasons and occasions to compel inquiry into these histories, both at the level of tradition and at the level of people who produce music, felt very important. So Sanctuary was intentionally designed to move through prayer and proximity. I tell people that every movement, in Sanctuary particularly, is a prayer, and every movement through it is the practice of the word.

Proximity is something that musicians, singers, and choir directors, and people in general who were living with HIV and died of AIDs complications, were refused, often, when they were dying.

The final section is Benediction. Benediction is a semicircle portal for the souls who have been deceased, who have not been offered ceremony and homegoing, to leave this plane of existence. I took the same keywords that were the basis for the songs in Sanctuary and found those keywords in the book, The Lonely Letters, my second book, and read passages that are centered on those same words. JJJJJerome Ellis played the strings and, as with Procession, I improvised on the Hammond organ. That twelve-minute song feels more lifting because the idea was to leave this plane of existence. It’s not as low and meditative as the Procession song. It has much more of a feeling of floating, a feeling of a kind of an ascension, but not an ascension to Heaven, but ascension to another way of life.

DW: I am so glad I started with this question, Ashon, because quite often we shortchange craft, and it’s great to hear all the thought and skill that’s gone into the making of this piece that you just so eloquently described. My initial impression of the piece, beginning with the first part, Procession, was immediately colored by the soundscape. The score you’ve created with the strings and the Hammond envelops you in a kind of ambient atmospheric sound. And, of course, the incantation of all these different names is so evocative. I kept on thinking how sound tunes our comportment.

AC: That’s a perfect way to describe it. The tuning of the comportment.

DW: In Procession, also, I really liked how the sound of the Hammond organ would punctuate the ambient composition and shift how we might have been casting our gaze, or how we might have been standing, or moving through the piece. In Sanctuary, the second part of the installation, we hear a more recognizable gospel sound, which, again, orients our relationship to the space in a different way. And in Benediction, perhaps because we hear words drawn from your book The Lonely Letters, because of the intimacy of those epistles, we again shift our comportment. All this to say, as we move through the installation, I appreciated how the sound of each piece hailed us, and reoriented our gaze and body, in a different way.

AC: I wanted there to be three distinct sonic signatures. That felt very important. As much as I love the sound of the Hammond organ and its use in the Black Church in a normative Black Church sound, I also know that that sound is very traumatic for a lot of people. So wanting the Hammond organ to be the through line, the instrument that connects each of the sections, was very intentional. The Hammond organ and the drums are the only instruments you hear in Sanctuary. But it felt necessary, too, for there not only to be the sound of a choir singing—because of the histories of what the performance of choir singing in churches has meant for so many people. A choir singing doesn’t just bring moments of joy. For a lot of

people there is also the sound of trauma and the sound of pain. So I wanted that to be there. I also wanted there to be a different kind of sonic signature for people who are either unfamiliar with the sounds of the Black Church or for people who are perhaps trying to find a relation to those sounds in ways that are less traumatic and more generative. I wanted to work with someone who could help me render different kinds of feel- ing and mood through sound. Working with JJJJJerome Ellis was really a gift because they were able to capture the kind of mood that I was going for that could be the basis for me to improvise on the Hammond organ. And so the chords that I’m using are chords that you would hear in Black Church services, except the foundation for it that JJJJJerome provides with the strings are not necessarily what you would hear within the context of a Black Church service, certainly not a church revival. It would be something much more akin to the experimental form that folks like Philip Glass and Steve Reich take. It felt necessary to have these different sounds, sonics, sound prints, footprints or sonic signatures, because different people could access the piece differently and have different experiences of it.

DW: I kept on thinking how you’ve used the sound of gospel music in your installation, and more broadly how you’ve come up with compositions, where the music itself serves as a sanctuary in a way that, especially for the people that you are commemorating, the church was not. But while the church may not have been a refuge for Black gay choir musicians reckoning with AIDS-related illness and death, the music they sang surely offered some solace, some comfort, became a sanctuary in its own right.

AC: They found comfort, and they performed it. They continued to write it. You’re right, song is sanctuary in a very explicit and intentional way, and trying to replicate that feeling where the music could be that, felt like the major urgency of the piece for me.

DW: The other notable aspect of experiencing HOMEGOING on the Mall is that it’s set on a stage as dramatic as one could have. When I went to see and hear the installation, it was a beautiful, breezy summer day. Not your typical muggy, humid August afternoon in D.C. While going through and listening to HOMEGOING, I can see the Washington Monument in the near backdrop, and beyond landmark government and civic buildings, like the Treasury and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And it was not just this vista, but there was also a distinct sound that was asserting itself that day. Not competing per se, but overlapping with the sound of your composition was the loud flapping of the more than dozen flags that encircle the monument. And I thought of the dissonance between the music I heard right next to me, and the one in the near distance, that is the sound of a certain kind of jingoistic patriotism. That dissonance was so powerful it exaggerated the underside soundtrack of a nation where many thousands died because of the government’s neglect of the AIDS crisis. The contrast of your artwork and the iconography of patriotism, the contrast between the incantation of the names of the dead and the sound of flags flapping, that juxtaposition was quite dramatic and affecting.

AC: The sound of those flags flapping was a constant. Whenever it was windy, and it was very hot most days, the sound of those flags was appar- ent. I wanted to produce something like a monument that wasn’t at all about heroes or a kind of patriotism. It wasn’t about, look at how great this nation is. It was both an occasion to celebrate, but not celebrate, in terms of a kind of militaristic victory. This isn’t a story of victory at all. It’s a story of heartbreak. I think that that is the American story, that what we continue to do as a nation is to produce occasion for heartbreak, because we refuse to reckon with the past. We refuse to be kind to one another on a structural level. You know, I’m trying to write this book about the Hammond, and I’m talking about unkindness as the major category that I’m using to analyze policy—because unkindness is what precedes the calcification of things into law. Can we produce an occasion to honor on such a national stage, on such a well-visited location? I’m actually surprised I didn’t say more explicitly that this is not about nation conceptually. It is not about democracy. It’s not about any of the keywords that get used to fetishize the United States as “the greatest nation in the world.” None of that. This is what happens when we don’t account for how unkind we are to one another. And that’s not to say that we cannot celebrate people or think about the beauty that people create in the United States. But it has to be done within the con- text of recognizing and reckoning with the ongoing nature of systemic and institutional practices of violence and harm. So it’s kind of like an anti-memorial, or anti-monument, because it’s not patriotism at all.

DW: I kept thinking about, as I’m sure you did, your work’s relation to other landmark protests that were staged on the National Mall to challenge the silence surrounding the AIDS crisis, silence that compounded the crises into a mass calamity. The easy reference, of course, is the AIDS Memorial Quilt, but frankly I thought about ACT UP’s Political Funeral and Ashes Action, where activists threw the ashes of their beloved dead over the gates of the White House as a form of both protest and commemoration. That action has a different, more powerful resonance, and I couldn’t help but conjure it up in relation to your work.

AC: Thank you for that, because everybody asks about the AIDS Quilt and how did the AIDS Quilt inspire you? I don’t want to be dismissive or curt about that, but the necessity for a certain kind of naming convention and the necessity for a certain kind of publicness of identity is really the foundation for the AIDS Quilt, not to say that it’s not important, but trying to think about people who have been lost whose names could not be said in the same kind of way. I’m teaching both Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten and reading their work these past two weeks, Scenes of Subjection and In the Break, which is a critique of subjectivity. I’m trying to question this situating impulse towards the individual that has to be remembered over and against everyone else.

Dumping the ashes on the White House is about both the public- ness of loss and the refusal to let that happen without response. But it’s not the same kind of celebration. It’s much more about grief and the lingering nature of grief, and a literal attempt to confront things like the Washington Monument and the stories that the nation tells about itself—like that which emphasizes victory—while also trying to maintain a certain level of anonymity for the musicians I’m thinking about.

DW: I was telling you that your piece meant so much to me as someone who came of age in Washington, D.C., for whom Black gay bars and clubs like the Bachelor’s Mill and the Delta were deeply formative as they were, I’d imagine, for the men you commemorate in HOMEGOING. I’m thinking also of what Darius Bost teaches us in Evidence of Being, the unacknowledged but important role of D.C. in the late 1970s in ushering in the Black gay cultural renaissance. We associate this renaissance with the onset of AIDS, but he predates it to publications like Blacklight founded in D.C. in the ’70s and to the political mobilization around the killing of a number of Black trans folks in the D.C. area. I couldn’t help but bear this history in mind, seeing your work staged on the Mall, in Washington, D.C. Also, as an HIV positive man, your work spoke to me in an immediate way, both in the way it honors the AIDS dead and speaks to us now…

AC: In the present.

DW: Yes, in the present, given the AIDS crisis is still ongoing and unfolding. I was moved by all of these different layers and resonances that your piece evokes. I should also say that while listening to Procession, in particular, I thought about the distinct aesthetics of Black gay artists of the 1980s and early ’90s like Marlon Riggs and Essex Hemphill. There is not merely an inter-textual relationship but an inter-textural one between your work and theirs. The way you orchestrate and layer the incantation of the different names of the dead in Procession calls up, for example, Riggs’s brilliant use of montage or Hemphill’s equally brilliant use of choral poetry as a way to overlay and echo sound. I’m thinking of that famous chant, “Brother to Brother Brother to Brother Brother Brother to Brother Brother to Brother Brother…”

AC: You know, I didn’t think of that, but I do now. It makes a lot of sense. I’ve been returning to that work and reading Evidence of Being. It was really helpful in getting me towards the argument I’m making that these were very specific artistic practices of people who were dying. And it is not a history that is distinct from the history that Darius is covering. This is that same history, and as I already said to Darius, this is not a critique of his work at all. But because of the way musicians within this domain get called religious, and because they do the work within the space of the religious, the religious actually short circuits a lot of the ways that they could be understood as engaging in the same sort of existential crises through art making as a way to confront, or at least ask questions about, the meaning of life. These musicians are recording over and over again before they’re dying, and it was very difficult to record in the ’80s and the ’90s. You couldn’t release things on Soundcloud the same day like you can now. So there’s a way that the kind of regularity with which they’re producing music, for me, just shifted when I read Evidence of Being, because I have to actually pay attention to the fact that they’re doing so much within this context at this time period.

These musicians are recording over and over again before they’re dying, and it was very difficult to record in the ’80s and the ’90s.

And his work helped me to think about that. In Procession I wanted there to be the names, but I didn’t want the names to all be read in the same voice. I wanted them to sound different. I wanted it to be textured variously. And part of the echo and the whispering was about a theme of haunting, a theme of ghosting, a theme of lingering, and a theme of suggestion—some of the names you hear only as a kind of suggestion or intimation. The use of both the full voice, but then also the quiet, the whispered voice, is about intimation. It’s about intimacy. And it’s about using the textures to compel people who are there to actually pause and try to really listen to what is actually happening. Some people will just walk and move through it quickly. And that’s what they do. But so many others just sat there and said, oh, these are names. They’re actually names. And so thank you for at least noticing that multitexture.

DW: When we saw each other in D.C., we talked briefly about Sojourner: Black Gay Voices in the Age of AIDS, an anthology by the Black gay artist collec- tive, Other Countries, published in 1993. The first three pages of the book list hundreds of names of Black gay men who died of AIDS, name upon name upon name, a serialization that creates an incantatory readerly experience. Which is to say, again, I appreciated how you invoke the names of the dead in HOMEGOING and also allude to antecedent texts. But let me pivot a bit to ask you about HOMEGOING in relation to your books, Black Pentecostal Breath and The Lonely Letters. One key thread is the way your work brings the spiritual back into our critical discourse. Your work deepens our conceptual understanding of the spiritual and enlarges the critical frameworks of contemporary thought. Can you say more about how the spiritual or spirituality has come to inform your body of work?

AC: Thank you for saying body of work. It still feels like unreal or surreal. None of this was planned. None of it was the intention. I just wanted to teach. I enjoy teaching and writing. And now I enjoy the artistic practice. No one believes me but I’m a bad academic, and I don’t know how to think according to the disciplinary life. When I was in undergrad finishing my thesis, I was talking to someone about some photos I had taken of some kids. My undergraduate thesis was about educational inequality, and I was doing some volunteer work at a charter school. I didn’t know charters were bad then. And so my thesis has photos, stuff from my architecture classes, and it had the writing in it. I thought that I was getting away with doing one expanded project, and that the professors didn’t know. I thought I was sneaky. I probably was sneaky. But actually, I was doing interdisciplinary work from the very beginning, and I just had no idea that that’s what I was doing, because I think that problems are interconnected. That’s just how my mind works. What’s the relationship between this thing and this other thing? So in everything I do whenever I write, I’m always thinking about the relation of whatever that writing is to something that’s being performed, if it’s being sung, for example. What are the various ways that you can say this thing that can meet different audiences? I get a lot of this, and rereading In the Break just reminds me that a lot of my inspiration is Fred Moten’s work. The way he finds different ways to say the thing that he’s trying to say has always been inspiring to me, and I think that it’s the impetus for me to try differ- ent practices. You know, my parents aren’t going to read all of Black Pentecostal Breath, not because there is a lack of interest, but because if you don’t read Kant, a twenty-page rant about Kant, whatever chapter that is, it’s like, I don’t care. And I’m not mad. If you don’t read Marx, then that section about Marx isn’t going to speak to you. There are some things that were being done in that book because I had to do it for academia. Is there a way that I can make these same arguments in a different form, where you don’t have to read Kant at all and make the same argument? For me it’s both a challenge, and it’s not like the challenge of what people degradingly call accessibility. I’m not trying to make an argument that this needs to be accessible. I have no anxiety about writing academically. But I do think that we can write in various forums, so I’m trying to figure out what the methods and strategies are to say these things, to make these arguments, to engage audiences. That actually feels very, very important to me. Artistic practice has been one of those things where I can try to figure it out and try to think. But because it’s like a painting, there is no conclusion. But you can engage and think about color, placement, and texture. For me the question is how do we get people involved in the things that we’re doing? Trying to do it in different genres is exciting to me. I’m an experimenter and like to try things. What happens when you do it this way?

DW: And we clearly hear it in HOMEGOING, this impulse to experiment. In Benediction, for example, you’re drawing on your book, The Lonely Letters, an experimental work that uses the intimacy and vulnerability of the missive form to do the work of high theory. And the excerpt you’ve chosen for Benediction is imbued with a kind of intimate wondering and wandering, while also deploying and citing theorists like Fred Moten.

AC: There were some passages where I said to the studio person, we’re not keeping that. Because it felt like this was a little bit too much—I wasn’t reading the entire letter. And I was a little bit skittish about even leaving the ones that said Moten and Denise DaSilva’s name. People are going to be walking by and hearing this, and I’ve been really surprised by how many people say I cried at that. I thought, you cried listening about Fred Moten? OK, let’s do it. Let’s do it.

DW: Because the theory is situated in a different context, and perhaps this might also be a difference between Black Pentecostal Breath and The Lonely Letters. Because the latter book brings together theory, biography, your words and your visual art—it has a different emotional and conceptual feel.

AC: I started painting in 2017, and I started writing those letters in 2010. I started editing the letters into the thing called The Lonely Letters at the end of 2016. At that point, there was no plan on painting anything. It was just going to be some letters. I moved to Virginia, and I had a lot of free time, and I said, I need to do something in my free time. And I started painting. I do want to return to your question about the spiritual, though. Only because there’s the phrase “spiritual but not religious,” and I really hate that phrase for a lot of different reasons. People say they don’t like organized religion. I’m okay with being organized and having formed together with other people, which for me is organization. I don’t think there is anything intrinsically negative about the organized aspect of organized religion. I think it’s the doctrinaire and paternalistic aspects of it that make it such a problem. What I have been trying to do is think about Blackness as a spiritual practice, and not a religious practice. And I’ve been trying to say it in ways that make sense, like the Black Church is a consequence of relation, not doctrine. One of the problems we are in the middle of is that there has been this deep conflation of doctrine with relational practice, so that people think that the Black Church is the right institution because it has the right doctrine. But no, it was a good institution because it allowed people to gather, and you knew that people would be there. You knew that it would be open. You could get a meal there. But it was just there. That is different than saying, “The doctrine that we have is the correct doctrine, and if you don’t believe this, then XYZ…” So I’ve been trying to think about a non-reductive way to think about various traditions as all participating in Blackness and giving us a way to under- stand Blackness as a spiritual orientation that is both about the material world but that is not beholden to the tangible, that recognizes deep connection, that accepts spirituality. And so I write a lot about Islam, because I think it’s important to think about the foundations for the thing that we call the Black Church not belonging to the thing that we call Christianity. That is an actual gift, because it should give us a way to be in relation with people who are not Christian, but instead there’s Christian doctrine that allows you to appropriate everybody’s stuff. I’m totally against that. One of the reasons why I’ve been trying to think about and practice spirituality is that I’m agnostic most days and atheist the other days. I’m not making an argument about people needing to convert. But I do think we need to become spiritual, and I think that there’s a deep worry over spirituality. It’s not only because of religious trauma, but a lot of the concern over how the spiritual is classist and elitist. It’s like the idea that spirituality is itself backward. And that it is just a consequence of a certain kind of cultural elitism—I’m not into that. I’m trying to stay in the place of spirituality while thinking with people who are religious and not requiring conversion, and thinking, is that even possible?

But I do think we need to become spiritual, and I think that there’s a deep worry over spirituality. It’s not only because of religious trauma, but a lot of the concern over how the spiritual is classist and elitist. It’s like the idea that spirituality is itself backward. And that it is just a consequence of a certain kind of cultural elitism—I’m not into that.

DW: You’re a theorist, a scholar well situated in Black Queer Studies, Sound Studies, and Performance Studies, to name just three fields. You’re also a sound and visual artist. I don’t want to make a false distinction between these two facets of your vocation. But when I look at your work, I am reminded of how we are moving in a different direction in these fields and opening up new horizons. Not to mention, there seems more leeway in the academy now to produce books and projects that diverge from the conventional academic monograph. It’s more of an open-ended question, but I’m curious to hear you reflect on what new possibilities, say, a field like Black Queer Studies makes available to us.

AC: I think there is a crisis of meaning when it comes to questions about the spiritual and questions around gender and sexuality. I said this in a podcast a couple of years ago that Paul was an apostle, and not to the Jewish people. He was an apostle to gentiles. He was saying, I’m talking to y’all who think you’re right. I feel that there is a way that people on the left, people who are progressive—this is in academia, certainly—think they’re right about everything. And I think that I noticed a lot of crises around gender and sexuality. I notice that a lot of folks’ need for gender and sexuality to be biological, is a symptom of the larger problem that I think Black Queer Studies is helping us to sense, which is that there is such a deep worry over the meaning of existence, and for those who presume themselves to be on the left, who want to be good progressives, they’re like, I accept gay people. I accept trans people. And they think that their acceptance is enough. They think that what acceptance means is a certain kind of distancing by saying, you can do whatever you want to do. You can be whatever you want, and that has nothing to do with me. And it’s like, no, actually, what we should all be learning is that we perhaps don’t know what gender is, and that the strictures that have been placed on us, that trans folks and gender nonbinary people have been making more explicit for us, is not just a question for them. It is a question for us all. And I think that we are existing in a kind of a spiritual crisis because people know this, and they refuse to accept it. What Black Queer Studies can allow is an interrogation of these sorts of carceral logics that we place on the body because we find them useful, because we find it necessary to not ask ourselves or examine ourselves and think of ourselves. Perhaps we need to be changing at the level of the individual as well as becoming more open, more capacious, expand- ing our horizons for what might be possible. We’re deeply afraid to do that. And we think that it’s the responsibility and the job of those people to do it, and if my kids are that way, that’s fine, but it has nothing to do with them. And I’m like, no. Black Studies is for us, by which I mean the world. Settler colonial interrogations are not just for people who are indigenous or whose lands have been colonized. It is for all of us to relearn our relation to earth and land and self, and we stop short of that final part in all of these different areas because we think that the problem is always out there. My hope is that what I can learn and apprehend from Black Studies and transness, Black Studies and queerness, Black Studies and gender, Black Studies and sexuality, can actually allow us to rediscover our sense of purpose. That we’re not here for academia, that what we should be here for is change. It’s a simple thing, to change the world, but not in a let’s just open a new center or change in that kind of way. No, it’s like how are we actually rediscovering who it is that we say that we are as a collective, and how can we practice a real liberatory project, both inside and outside the thing called the academy?

No, it’s like how are we actually rediscovering who it is that we say that we are as a collective, and how can we practice a real liberatory project, both inside and outside the thing called the academy?

DW: You remind me of something James Baldwin once said in an interview, that the white liberal is akin to the colonial missionary. Both stay wearing their paternalism. Both are keen to save “the other” instead of worrying about and working towards their own salvation.

AC: Every time. And it’s like, why is my air conditioner on? It’s like, it’s cold outside. I might have been laughing, but I’m actually really concerned, honestly, because the violence that gets called not-violence amongst the people who are so called progressive and liberal is really a problem. They think that there’s this way that as long as they accept you, they still get to occupy the paternalistic center, where they get to be the measure of all that is and is not good, the measure of all that is not proper in terms of gender. As opposed to actually knowing that is wrong. There is almost this stranglehold on both being good people and right and refusing to actually do that kind of self-critical examination. So it makes me wonder, what are you all actually reading, beyond just reading it? Or are you just saying it, so that you can check off a box? And it becomes really concerning because these are the same things that other people do, and shit turns violent really quickly.

DW: Absolutely. And yet there’s so much grandstanding in the academy, and things we just say by rote, or because something has currency at a given time.

AC: There’s a lot that has currency.

DW: Well, last question, and I want to return back to sound. I wonder, what are the particular prerogatives of sound? I ask in part because I love reading poets like Douglas Kearney, M. NourbeSe Philip, Harryette Mullen, Dawn Lundy Martin, and other experimental poets who disorient the conventions of ordinary language. Their work frees me up from the tyranny of semantic meaning, and instead allows me to heed sound for its own meaning, its own properties, without the telos of semantic legibility and coherence. I’m wondering, given your sustained preoccupation with sound, how you conceive of it and how you deploy it to reach that higher ground?

AC: I think that sound is a thing that connects us. Sound is heard because of vibration, and vibration, even for people who don’t hear, is something that can be felt and registered in the flesh. I love sound, because the sound of church is the thing that made me happiest. The vibrations of the tambourine and the foot stomps and the hand claps and the Hammond organ, that was what gave me joy more than any- thing as a young person. There was something about the sound that isn’t tied to doctrine. It’s not tied to a theological orientation. It’s tied to a kind of openness to being moved. And so for me what sound does is open us to sound and allow us to rediscover all of our sense capacities and their variousness. We don’t say that sound is better than or more precise than other sense experiences, but that sound is sensual, or hearing is one sense experience amongst others, and that sound is one of the ways that we can be in relation to one another. So, thinking about the sound of Islamic prayer as the basis of the blues, gives us a way to think about what relationships can be had and can be considered. What can we construct in terms of people who are Black and Muslim, people who are Black and Christian, people who are Black and atheist? Can sound be a way to connect us to one another? I’ve been trying to perform that in my work. I’ve been trying to say that the answer is yes, it can connect us. And so, you know, I love sound because it’s difficult to contain, and it can feel really good.

DW: Ashon, I am immensely grateful for this conversation, and of course for your work, which brims with wisdom. Thank you.