by Robert Reid-Pharr, Editor

I always felt that when I was talking publicly, I was talking mainly to the children, to the young, which is as to the future, and I was talking about people’s souls; I was never really talking about simply political action, because I am not a political activist.

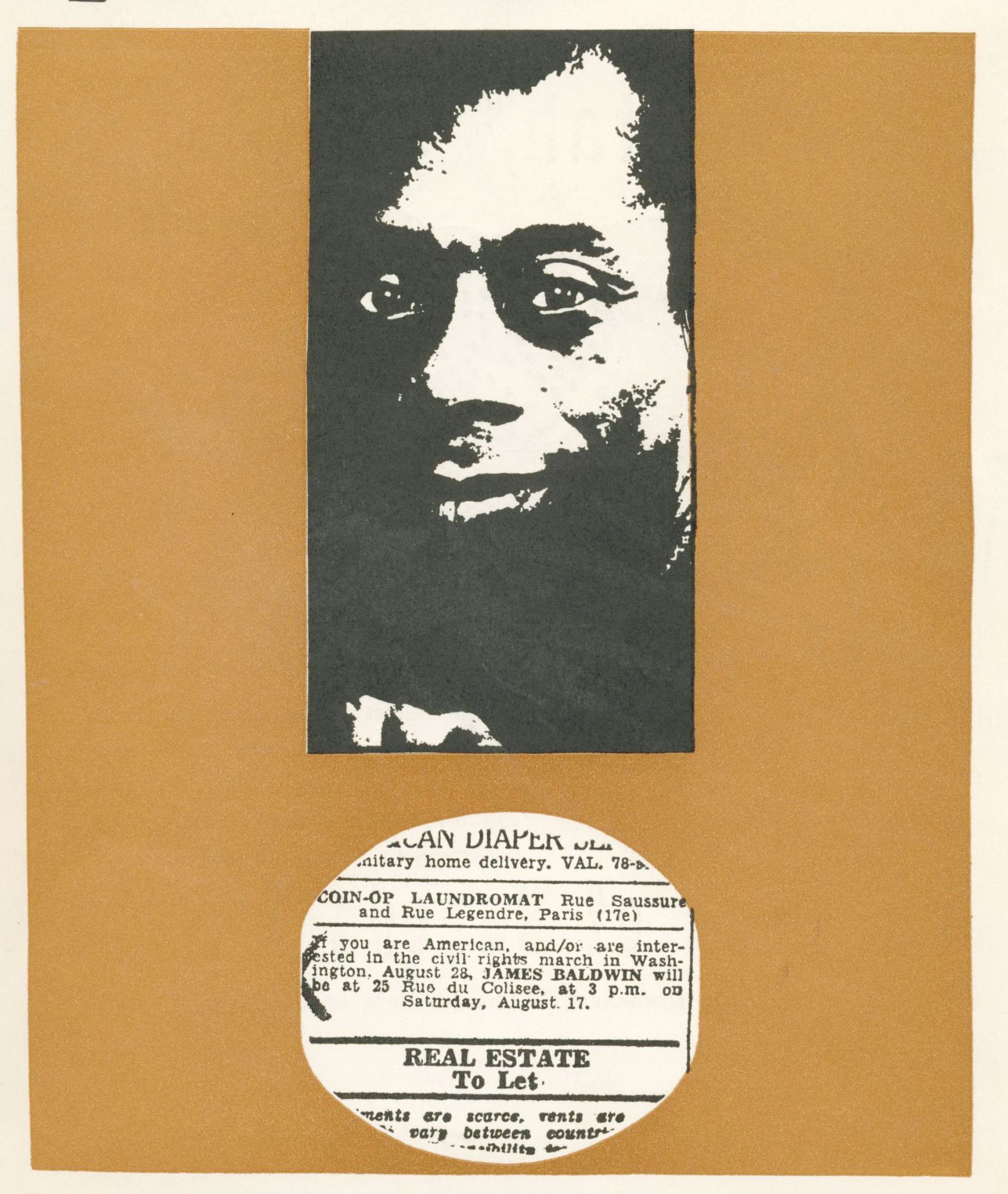

—from James Baldwin’s interview with John Hall, Transition Magazine 41, 1972

There is a funny thing about movements. They never really seem to be about us. Abandoning the comfort of home, leaving behind harried partners and pouting children, we gather in our halls and offices, hands full of flyers, hearts full of hope. And sometimes on extraordinary days when victory seems either impossible or just at hand, we turn toward the brightest and most talented among us, looking to them for knowledge and wisdom that will allow our many peoples to carry on just a bit further. Still, though these champions of cold struggle and burning hope warm our spaces with bracing intellect and fire spitting rhetoric, they always seem to cast their glances far beyond the dull environments in which they find themselves. Like Janus they never look directly in front. Where we have come from, where we are going, and the paths of our journeys are all that seem to concern them. The grandest of our intellectuals are necessarily aloof, pointing out the (imagined) way forward while often forgetting to fill in the details of how to get us, all of us, from here to there.

For more than fifty years Transition Magazine has been a primary location for (re)presenting the best of African and African Diasporic thinkers to the communities that produced them. The magazine has a particularly distinguished history of interviews with prominent artists and intellectuals. This includes two interviews with the African American writer and activist, James Arthur Baldwin (1924–1987), conducted by Francois Bondy and John Hall in 1964 and 1972 respectively. Both interviews are wide-ranging yet both take up the question of how black celebrities like Baldwin might contribute to the freedom struggle. In each instance, however, Baldwin demurs, claiming that he is no political activist and that his actions are always indirect. That is to say, Baldwin was not so much talking to his interviewers as he was to the past and the future, indeed to us. You are the person for whom these words were intended. Your interpretations are the ones that really matter. Yours is the soul that the maestro wills to be either saved or set on fire. Read well then. Let the strength of Baldwin’s stylish language fortify you. Then get back to work. It is time to prepare your own words, time to make your own earnest statements to a future that is still not quite imaginable.