Freedom Is a Gathering Place

by Kara Blackmore, Helga Rainer, Gloria Kiconco, Charity Atukunda & Elsadig Janka

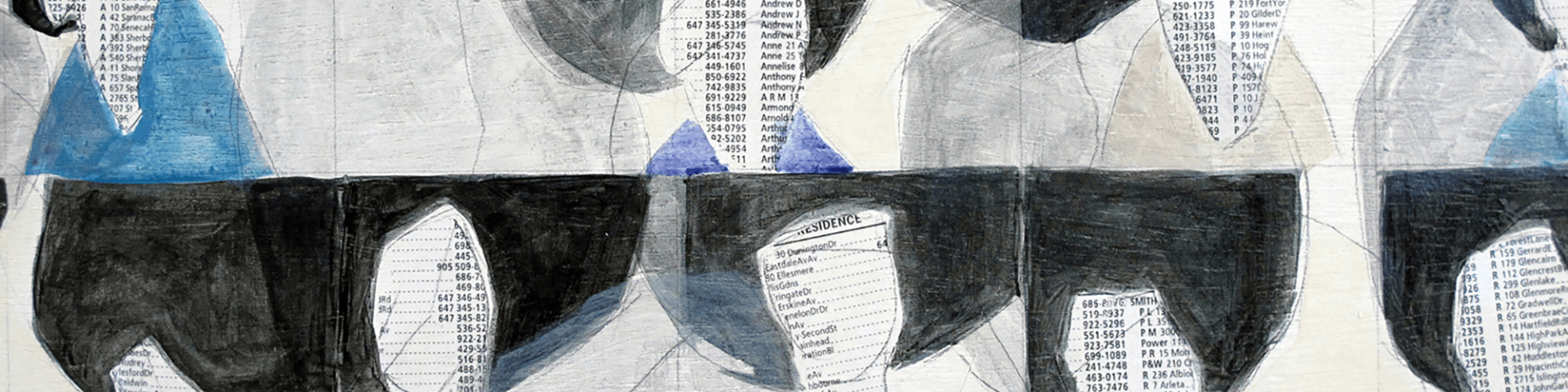

In Uganda, artists are asking: “Do we have the liberty to disagree?” This question underpins the series of artworks created for the Send Me exhibition held in Kampala in 2024. Socially engaged artists and curators used the exhibition as a staging ground to form solidarity between Ugandans, Sudanese, and the residents of the city. Gloria Kiconco, Charity Atukunda, and Elsadig Janka each made new artworks to create biographies of place, reflect on the movement of ideas between those places, and finally to ask questions about aspects of security. Their work oscillates between deeply intimate storytelling and geopolitical critique, opening a creative space that reveals strategies for solidarity, which are not always public, but traded between networks and encoded in symbols.

Transition Magazine’s archive was a central artist resource. The historical publication—founded in Uganda in 1961—provided a framework to question liberation. In this way, the magazine was a companion text to both inform our curatorial process and a touchstone for creating new artwork.

Photo Credit: Martin Kharumwa.

For ten years, Transition was produced during a period of fundamental change across the African continent. The magazine gained a reputation as a significant platform for East African writers and Pan-African intellectuals, including Nobel prize-winners Nadine Gordimer and Wole Soyinka as well as Ngugi wa Thiongo, Chinua Achebe, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Julius Nyerere, and Ali Mazrui. African and African American writers within Transition Magazine formed bonds by exchanging thoughts regarding questions of blackness and the conditions of the postcolonial. The tenures of key writers at Makerere University, and their publications in Transition, made Kampala a significant intellectual centre at this time, playing a role in the rise of the publication’s prominence.

The magazine’s willingness to criticise the challenges associated with the post-independence period across Africa reflected the editor Rajat Neogy’s belief that Transition should be a publication that holds a mirror up to society. Its presentation of often provocative content brought the force of the Ugandan government against Neogy, who was jailed in 1968 for sedition. The government justified its search of the publication offices and imprisonment of its editors because of its criticism of President Obote’s proposed constitutional reforms and the revelation that secret funding from the CIA had made its way to the publication through the Farfield Foundation.

Once its founding editor was jailed, Transition Magazine’s ability to freely criticize the status quo was severely curtailed in Uganda. The publication moved to Ghana; shortly thereafter, Wole Soyinka took the helm as editor. His statement “The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism” aptly reflected Transition’s journey.

Art. Photo Credit: Martin Kharumwa.

Despite the online archive of Transition and its international acclaim, it is not well known in Kampala. Even those who are aware of its existence, know it mostly for the acclaim it has garnered rather than the content of its pages. Some issues are available in libraries across the city, and scholars have cited the publication, predominantly when referencing historical events that took place at the time Neogy was arrested.

Fast forward to 2024, the three artists, Gloria Kiconco, Charity Atukunda, and Elsadig Janka, worked with curators to engage the texts of Transition and question their salience in the contemporary contexts of Africa. Looking back, they could see an atmosphere in Uganda that was marked by a continued crackdown on those who had criticised the political ruling elites. Scholars have chronicled how the freedom of the press has been systematically under threat in Uganda for decades. Despite the growth of media houses under President Yoweri Museveni—who took power in 1986—this proliferation of outlets has not equated to more freedom of speech. Instead, artists and intellectuals have increasingly been silenced and imprisoned during Museveni’s tenure. Former Makerere University academic Stella Nyanzi was arrested, tortured, and imprisoned for posting on social media about the president’s mother. Another important figure who has been repeatedly targeted by the Ugandan government is the musician turned opposition candidate Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, popularly known as Bobi Wine.

In working with the archives of Transition Magazine, we recognised the recursive histories of oppression in Uganda. At points, it seemed easy to feel a sense of déjà vu while reading about the 1960s during Obote II or the 1970s when Idi Amin violently cracked down on artists and intellectuals for their outspokenness, while at the same time expelling citizens based on their South Asian heritage. Monitoring agencies who observe the state of artistic freedom globally continue to list Uganda as one of the most dangerous places for artists. Artists who engage subjects related to LGBTQ issues are some of the most scrutinised, often being surveilled, threatened, or violently attacked by government agents as well as Christian fundamentalists. And yet, creativity continues.

In this context, Transition was put in conversation with artworks created in its birthplace, Kampala, Uganda. Audiences coming to the exhibition would enter through the “Best of Luck Duuka.” This installation, which invoked the aesthetic of a small roadside shop, was designed with the familiar materials of plywood and tarpaulin and adorned with a pasted collage of selected covers from Transition Magazine. This aesthetic of a “flyer-wall” was a staging ground to choreograph movement between time periods; 1960s and 70s magazine covers were pasted beside shop shelves displaying the familiar goods found in Kampala’s duukas: bundles of simsim balls and peanuts as well as sachets of soap and muchuzi mix. Going through the corridor of the Duuka simulated an entry point where street and home might intersect.

Rather than defining individual zones of display for each artist’s series, the artworks were presented in an open and connected way. This was an overt reference to the artists’ collaborative process and shared points of view. We wanted the audience to feel the links between Kiconco, Atukunda, Janka, and Transition Magazine. We also designed a somewhat “familiar” aesthetic of display as an intentional rejection of the white cube, noting the inadequacies of the commercial art scene within Kampala to stage such conversations. For example, Atukunda’s Fashioning Freedom and Kiconco’s Cardinal Directions were partly displayed on concrete blocks that were a feature of the barricades that Janka saw repeatedly on the streets of Khartoum during the Sudanese Revolution.

Transition as Critical Companion

Kiconco’s Cardinal Directions is perhaps the most overt conversation with Transition Magazine, with four zines entitled: “North—Those Who Return,” “West—Those Who Wander,” “East—Those in Exile,” and “South—Those Who Stay.” Making direct references, the zine provides a sense of possibility and connection that is essential for creativity because, according to Kiconco, “If you don’t feel delight, if you don’t feel possibility, then you don’t even feel that you want to express yourself.” In the depths of despair created by oppression, sometimes it’s hard to say anything at all because you wonder: what can I say, for whom, and why? In this series, the cardinal direction speaks to a shared human need for direction, whether that direction means having a moral compass, a purpose, or a desire, including the simple desire to connect with another.

Reflecting on freedom as a migratory process, Kiconco notes that some stay, some leave, some give up, and others slip into the background. This zine series reflects the relationships people have with time, place, and text. Each form reveals a different set of concerns that have been articulated through interviews Kiconco conducted or come from her own experiences as an artist, poet, and writer. One issue that arose was that of choice. Is staying or leaving actually a choice? Or is choice just an illusion? The impacts of the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act, which are now hardened into law, have surpassed other moral laws such as those around modesty and pornography to criminalise the existence of LGBTQ people. Such cruel legislations and the violent populist actions that align with them can make life, and particularly life in Uganda, feel impossible, and yet many are left with nowhere to go.

The directions were a useful device to position experiences. Using constellations in the drawings reinforces this idea of relationality whereby one can see one’s self reflected in a certain direction but somehow not alone in that journey or narrative. For example, “West” itself is very symbolic of western privilege. And a lot of families, who have the privilege of coming and going, most often, go to the West, as opposed to the South or East. Well, they also go to the South and to the East, but are more likely to live or create a base of operation in the West, in the U.S., Canada, or the U.K., which allows them relative ease of movement and expression.

Each zine describes different places where people have settled but these zines share a common theme. During the process of making them, Kiconco found that one’s sense of freedom changes according to one’s movement. One’s relationship to freedom changes with location and perspective. One interviewee described to Kiconco how they could imagine characters in their writing in Uganda but couldn’t fully articulate them until they moved to Canada because there was a barrier to the ability to create within the chaos of Kampala.

The complexity of being situated in Uganda is perhaps the most profound in “South: Those Who Stay.” Those who are invested in the project of social and political critique ask themselves a perpetual question: what would our creative landscape be like if Transition Magazine had stayed? The trajectories of travel in relation to Uganda are thus revealed, each within the folds, the ink, and the layers of the zine. Moving between the foundational period of Transition Magazine and the contemporary moment, the artworks serve as both a place of critique and a moment for playful connections.

Art. Photo Credit: Martin Kharumwa.

The medium of sculpture invites dialogue and also allows space for light, proximity, and openness, which is normally compressed in two-dimensional print features. There is an expansiveness in this series that comes, in part, from the conversations between the curatorial team and the artist, which encouraged the artists to push boundaries and find the edges of their practice. In the labour of finding the edge, one must be held and cared for. The communal acts of gathering helped to provide a scaffolding for that edge, so that it could be explored, rather than simply act as a cliff that one could fall off.

The series thus enmeshes Kiconco’s own experiences with voices from Transition and Ugandan artists who cannot openly share their perspectives. This is clearly defined in the “Dear Reader” blackout poem created from a letter written by Rajat Neogy. Kiconco’s version reads:

Dear Reader, I am sorry / I was / arrested/ I was arrested/ Mayanja and I/ charged with sedition / a couple of paragraphs / Judgment / Detained without trial / The Emergency / ever since / Held without trial / Before the trial / My home / searched / during and after my arrest / family photographs / removed / I was released / Abu Mayanja is still there / I cannot return to / the country of my birth / citizenship / cancelled / an alien in your own country / a betrayal / free and informed discussion has never overthrown any government / free press / free society / home is also all Africa / I am thousands of young / people in Africa / I have no / desire / than to live a normal life / keep in touch / I am / all of you / RAJAT NEOGY

Gloria Kiconco, North – Those Who Return. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Borderlands Art.

Photo Credit: Martin Kharumwa.

This piece is perhaps one of the most resonant artworks to bind the past to the present. We can imagine many of our artist friends and colleagues having written this. We connect to and want to respond back to the phrase “I am all of you.”

“Fashioning Freedom,” by Charity Atukunda, was a response to the societal structures that define the parameters of freedom. On one level, Atukunda recognised the glaring masculinities in Transition’s early editions, which made it hard to create a solidarity with the content of the magazine. She reflected on the overall dynamics at the time, noting that there were not a lot of women in higher education let alone the arts, even if it was a woman who started the arts department at Makerere University (Margaret Trowell in 1923). Atukunda started to investigate the gender disparity after finding only a few names like Teresa Musoke, Abubakar Fatma Abdullah, and Rebeka Njau amongst the dozens of men writing at the time. She asked, “Who is part of the conversation on identity, freedom, and nationhood?”

Just because women are represented in today’s politics does not mean that we are liberated. Fashioning Freedom emerged as a commentary on the assimilation to patriarchal power nested in political and social hierarchies. Women in this way have been maintaining a status quo rather than opening up more places for expression. A dance between the grassroots women’s work and the power play of elites finds some kneeling in reverence and others standing up. Yet there is no marching in protest. Atukunda recognises that there are more subtle and embodied acts of resistance as well as digital pathways for solidarity.

Gloria Kiconco, Dear Reader. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Borderlands Art.

Photo Credit: Martin Kharumwa.

Atukunda uses camouflage as a way for her to define the feminine power of concealment. Given that wearing camouflage print in Uganda is illegal, Atukunda embeds women’s acts of everyday domestic work into the print. From afar, the fabric appears to be a green military camouflage, but up close, one can see women cleaning laundry, cooking food, or pounding grain. A reminder of the tension between resistance and compliance was revealed when Atukunda went to get the fabric printed in Kampala. Amid protests against taxation and shop closures, she had to make sure no one mistook the fabric for an illegally produced military uniform or rebel combat fatigues. This experience shows that the artist is not only commenting on the realities but also the one taking risks for that creative critique.

Atukunda brings her drawing into her textile works and also proposes a figure showing both a gendered and embodied way to understand freedom. This artwork features a woman wearing a traditional Gomesi or Busuuti with a Kanga made of everyday material, thus drawing our attention to class divides. The woman in the Gomesi is presented on mukeka (traditional mats); a wide sash tied at the waist transforms into exaggerated long arms exchanging money. In the Fashioning Freedom series, the garments worn in weddings or for special events alongside an everyday fabric for the Kanga sought to bridge that class divide. In one garment, Atukunda connects economic statuses to make a critique against those who create the status quo and maintain it, those who assimilate to it, and those who fall in line behind it.

Charity Atukunda, Seen but Unseen. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Borderlands Art.

Charity Atukunda, What Do They Really Think. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Borderlands Art.

Making the artwork in a feminine frame shifts the conversation from the Ugandan era of Transition Magazine debates, which focused almost exclusively on presidents and “big men” to freedom and insecurity. Atukunda plays with the aesthetics of the covers, inverting the “Man of Many Masks” from the cover of T41 to create a self-portrait. She explains, “We are forced to show one face in a society where oppression is a norm, we are forced to show one face externally, but there’s always something internally that we don’t really share with people, or we can only share in specific spaces.” In placing herself into the frame, and playing across the multiple masks, she redirects the gaze away from the man and beyond the exterior layer.

Janka’s photographic series departs from the works that reference Transition. This is in part because, aside from one edition dedicated to Sudan, the experiences of Sudanese have not been centered in the magazine. It is also because there was a pressing need by Janka to focus on what was in front of him, in the immediate proximity of his own neighbourhood. As he described, “I am realising that my Khartoum is behind me.

Sometimes freedom is just a dream. Much of Elsadig Janka’s work is about dreaming. Dreams are not just happenings in the imagination, they have also turned to actions including the staging of revolutions in Sudan. After small victories, however, the country has become inhospitable. Over a year since the 2023 civil war started, dreams have turned to nightmares. It is in this limbo between dream and nightmare that Janka created A House Away from Home. He worked with writer and researcher Amar Jamal so that he had a narrative companion to make sense of the work. Jamal became an invaluable collaborator in the process, lending language to the nuances of their experiences as Sudanese living in Kampala.

In this series, Janka tells the semi-autobiographical story of his own life in Kampala, alongside portraits of neighbours and new arrivals. Using his style of multiple exposure and editing overlay, the images tell of a disorganised place of being. Yet there is order and connection to home—keepsakes and everyday objects thread through the stories of place and life in flux.

According to Janka, “a face in a frame is perhaps all it takes to describe the notion of belonging.” He took notice of the personal items and materials brought by individuals from Sudan to their new settlement in Kampala, Uganda. Recognising the familiar and the essential, he started to document those materials that signify life in between: a Sudanese women’s thobe, a first aid kit, guitar picks, crochet threads, shoes. However, while making this photographic series, Janka and Jamal learned that things will not help recreate a house away from home because the items truly needed to build a house outside the home are not material; instead, one needs perception, imagination, creativity, and emotion to rebuild.

The idea of home itself involves not just a return to a place, but a repeated return to the same place, even if it is a “soul place.” In this repeated return, the endeavour is safety and survival. For Sudanese residents in Kampala featured in this series, home is not just a house, it also means a homeland/watan—the word watan means a piece of land in Juba Arabic. From this piece of land, whether material or spiritual, the self migrates on its cosmic journeys.

Migration is a sacred right. Freedom is also a sacred right—beginning with the right to choose your name, as Pac (one of the people featured) chose his new name, and extending to the freedom of clothing, such as Uncle Salah’s commitment to wearing his Sudanese robe, and to the meaning of freedom embedded in the sunflowers for Tanzeel, and the reggae for Nabhan.

In an effort to not reduce the stories of the characters featured in this series, we have dedicated a single section to each one of them and the objects they always keep close by.

Elsadig Janka,Tanzeel. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Elsadig Janka.

The guitar pick does not leave Nabhan’s fingers, even while he talks about the meaning of home. “Home is the band that was disbanded by the war, and if I had one wish it would be for us to meet, even for a rehearsal.” In his house in Kampala, Nabhan keeps a reggae flag showing Bob Marley in his house, along with a Real Madrid player uniform with Dani Carvajal’s signature, and lyrics describing a return to Khartoum, which he wrote, after playing a solo on eternal invisible strings. These objects actively show that Nabhan is not resigned to his life away but always in the midst of negotiating the game of freedom and finding the right rhythm.

Rafid’s parents were forced to leave their home in Omdurman five days after the war started. Their baby was just three weeks old. “What did I carry with me?” his mum repeats Janka’s question, “Just what Rafid needed for the trip, one item, his birth certificate”—that is what Shaza and Yasser believe saved them. They journeyed by boat between Sudan and Egypt, returning to eastern Sudan, then coming to Kampala. Having only this document with them allowed them to survive and will also be essential given their planned return to Sudan.

Pac the joyful was still in secondary school when the Revolution started in 2018. “It turned me into a human being!” The chants of the revolutionaries crowned his euphoric sense of freedom: the condition he had sought since his youth, when he chose the name Pac for himself, after Tupac. He left Sudan with a metal plate inserted on his upper right hand after an encounter with authorities. He said he also left with “a soul shattered by arrest. Home for me is the care, even by my younger brother, my comrades, they define the new life.”

Tanzeel’s yarn connects her dreams and realities together. The more her memory slides into traumas, the more the threads of her crochet become both stronger and more tender. These threads weave imagined homes beyond the oppression directed against women. Her house is filled with crocheted sunflowers, representing an eternal hope and an aspirational freedom. A conditional freedom necessitates Tanzeel’s struggle to create a sense of home, even if it is built of yarn. Uncle Salah’s home in Khartoum cannot be reconstituted, no matter how joyful the new place in Kampala has become. Even in his old place, he had felt alienated by modernity. He wants to wear the jalabiya amid the renaissance of trousers that has invaded public space. Salah is an enlightenment teacher, who not only taught girls in schools, but also planted useful food on his land in northern Sudan. His reprieve is in playing cards, finding poetic references in the hand he is dealt. He takes small sips of happiness every time the Queen of Diamonds card is shown in his deck.

Elsadig Janka, Uncle Salah. From SEND ME installation, 2024. Courtesy of Elsadig Janka.

Maryam has not known safety since 2003, the year war started in Darfur. She lived in continuous waves of displacement throughout the cities and villages of Sudan, Egypt, the UAE, and Uganda. During twenty years of displacement, she realized that even if the safety of home goes away, it is necessary to preserve memory and gain strength through it. On her last migration, the seventy-year-old carried two Sudanese thobes/cloth wrappers, one for prayer, the other for brightness.

Sumaia crossed the wild distance from victim to saviour. A rare transit that requires knowledge, conscience, and strength. These intangible sensibilities help her recreate a home away from home. In her attempts to settle in Kampala, she realized that the only thing missing was the house itself, always incomplete considering her life on the move. Her plant nursery in the neighbourhood of Nyala was a sanctuary of freedom. There her planted flowers are left to blossom in fading hope, reminders of seasonal life and the possibility of new growth.

Bringing these stories together creates a collective social portrait of different generations and individuals. The material references are also points of collection for Janka, who wants the viewer to consider what a person needs to experience joy, identity, and belonging. Even though stories of departure can be difficult and harrowing, the depiction of dignity in the photographs shows solidarity by not reducing each individual to a subject of victimization.

The artworks, Fashioning Freedom, Cardinal Directions, and A House Away from Home and the overall exhibition Send Me, which collects them, were created through a series of virtual and physical gatherings between the three artists, gallerist Helga Rainer of Borderlands Art, and curator Kara Blackmore. The artists also met on their own and with people affected by the content or themes of their research. As such, their artworks are layered with those interactions. Though the artists created three distinct bodies of work, they thought together and worked in relation to each other, creating individual and interlinked reference points that formed new paths or trajectories to explore. In a way, we sought to have a call-and-response format. There were alternating callers: for example, Transition Magazine was a caller, as was the curator—with the artists responding in different ways. The result was a loose-fitting collective responding to questions of freedom. The outcome of these gatherings is more than the tangible textiles, zines, or photographs. It is a series of throughlines that create proximity between historical and contemporary conditions of freedom.

Exhibiting for Connectivity

The curatorial proposition to make these commissioned works public led to a tangible and dynamic space for gathering. We premise Send Me on the notion that exhibitions are always becoming and therefore not static spaces to be reflective but active spaces where dialogue is essential. It is in this format that the artworks are remade in new contexts outside the studio. Relationally, co-production and becoming were featured in different ways throughout the space in Kampala’s Circular Design Hub exhibition hall.

Transition Magazine was conceived as the staging ground, a kind of symbolic host for the exhibition. In doing so the content of the texts and contextual issues allowed us to engage key questions of freedom and insecurity at a sideways glance. For some audiences of an older generation who remember a celebratory era of liberation and creativity, the connection to Transition and the exhibition’s questioning of freedoms was overt. In an Instagram post, one visitor wrote: [SEND ME] reminding us that we, like the 1960s can’t be despondent, rather we must continue to pour into our communities in the ways we can and hold our collective hearts with promise (25 April 2024 @ _umutesi). Conversations with our exhibition interns revealed that the younger generation (known as Museveni’s babies because they’ve only known one president) did not see an obvious need to interrogate our perspective of freedom today in relation to the past.

In February 2024, the artists started to discuss the real economics of freedom. The “Best of Luck Duuka” is a direct result of those conversations. A duuka, dukani, dukkān, if you are speaking in Luganda, Swahili, or Arabic, respectively, is a shop, most often an informal place where you can purchase just about anything, but almost always in small quantities. This space of exchange and display recognises the reality that freedom and mobility in 2024 is as much about resources as it is about laws. The “Best of Luck Duuka” represented the many places where tangible and intangible items are transacted. The material objects signified the costs of exile and the gift economies that people rely on to maintain security.

We called it the “Best of Luck Duuka” to reference those chance happenings that can lead to one’s success. In addition, when people must leave, they are often told “best of luck,” “bahati njema,” “bonne courage.” The shop is also a playful riff on the many shops in African cities whose naming conventions provide humour and joy. We invited audiences to leave an item or take one of the many things lining the shelves (peanut packets, coffee beans wrapped in banana leaves, sachets of soap, muchuzi mix, sesame balls) with them on their journey. We also invited them to wish the best of luck to someone who is on the move or pay homage to those who did not have the best of luck and were targets of censorship.

Like graffiti on the outside of a building, those messages inked the plywood walls. They were diverse—including commentary on religion, love, and community. By writing on the duuka wall, the audience members responded to the curatorial call, committing their own acts of solidarity. Here are some of the things they said:

Freedom is a right; it should not be taken for granted. The struggle continues. -Aluta Continua

We as a collective We are water. We flow with the tide that is life And reform ourselves to the shape of our circumstances (Unlearn—Relearn) -Evelyn Hilda’

May you find a home in yourself, the people you meet, the places you go. May Love Peace & Companionship find you. -4RM A FRIEND

These letters to an anonymous ally encouraging them to continue the struggle and the notes to comrades and items left behind for protection (feathers, amulets) show how audiences responded to the call for solidarity. These were emotional and empathetic gestures far beyond the generic notes often left in a visitor’s book. The messages were reminiscent of the exhibition’s title “Send Me,” which is a reference to mail art of the seventies and ways in which artists would send codes to each other to stay safe. Even today, we send each other small snippets of information via digital messages. Sometimes we courier things to places where postage has been dying a slow death. Across Africa, artworks can come in suitcases or with security warnings in encrypted applications. One trip at a time we deliver those small things needed to sustain creative practice.

Solidarities of Time and Place

Transition and magazines published in the 1960s and 70s have often been celebrated, however, these artworks show some of the gaps and the biases in what was often a male-dominated and foreign-influenced space of knowledge creation. Transition’s story is also a metaphor for creatives who have been born in Uganda and exiled to other parts of the continent—and who are now building legacies in the diaspora. Recognising Transition’s value, biography, and relevance today shows a kind of solidarity with the past although through each section of this collection, new questions about our future direction emerge. As we question these directions, one thing is clear in the singular flow of thinkers and creators leaving. The brain-drain slowly drips by choice or by force.

Solidarity, for artists working in this context, is a way to bond but also a way to stay safe. Staying safe is not playing safe or being censored. Rather, all of the methods used by the artists and curators occupy a place of what Neogy proposed as a “do-culture: permissive, experimental, vigorous, and challenging” (Transition 24, 1966). Each body of artwork in Send Me provides a different register for inquiry. Here we recognise each artist’s journey as a space for continued creativity given the unique challenges to freedom of expression in Uganda and Sudan.

We choreographed a simultaneous expanding and collapsing of time. The gendered and patterned interplay of Atukunda’s traditional Gomesi and Busuuti with the camouflage material used to make them. A collage of voices from 1960s Transition magazine articles to interviews with contemporary collectives by Kiconco, presented with gaps and folds in the semi-transparent barkcloth paper. The photography by Janka that stills the chaos of unfinished revolution, pausing the rapid escalation of uncertainty in exile. Even the title of the exhibition is an ode to Sam Cooke’s 1957 hit You Send Me—the title curator Kara Blackmore gave the exhibition this title because she wanted to reimagine a lyrical longing for freedom, an aching for a thrill, and also recognise the infatuation with security, and the desire to be held.

Each aspect of this work, the making of the new artworks, the display of the works, the dialogue around the work and the reflections in this essay invite a much bigger conversation relating to artistic freedom and freedom of expression. However, our continued archiving of the process through this text and the artworks themselves align historical issues with the formation of solidarities in the present day. They reveal a new set of questions for consideration. In this time, we have also created a reimagining of the role of Transition Magazine as exhibition host and artistic resource, propelling it into connection with today’s struggles for epistemic liberation in Uganda.