The Levee

Stanley Stocker

They say the boy is brave that travels up the highway independent of his people. But I know it’s having them anchoring him at home that allows him to set off. A boy can branch out when he’s got his people to anchor him. That’s why one early morning, me and my dog, the General, left out to see a new part of the world, leaving my ma’am and daddy behind us, sleeping.

A boy can branch out when he’s got his people to anchor him.

We walked a long while, using the river to keep us company, all the way down out of Tekakwitha County into Cherokee. Slept out under the night and stars. Made camp with some roustabouts on the river near Leveetown. Ate with ‘em, talked, shared some scaugh. They like a boy that means to travel. Puts ‘em in mind of they own beginnings. We passed a day and night there. Hopped a steamer round Midnight and the river carried us down around Natchez. We stood on the bluff and watched the steamers rolling up and down the river. Outside Natchez, me and the General walked along the road then sat a while, watching the people pass by. Fellas going to market. Cotton. Big ole wagons full. Hogs looking out from the back of great big ole wagons. We walked along down the road and passed by this house. Damndest thing I ever seen.

Took me a bit to see it. It was right there in front of me though I ain’t see it at first. We were standing there looking over the place and I hear somebody calling. I look around and there’s a man waving his arms from the portico of the grand house. I turn around to the road but he steady calling and waving, beckoning me to come on up. So I open the gate and go in. Road to the house covered with these white shells and it’s crunching under my feet as I go. The man steady waving me on, “C’mon, c’mon. I could use your help,” he say. “That’s right, c’mon.” I saw there were two fellas up on the portico. The one calling hands in the air, the other fella sitting with his face pressed in a book. He never looked when I got there.

“Son,” the tall man said, “do you remember your Latin? You studied Latin, haven’t you? ‘No, sir,’ I say. Then the little man looks up from his book, and they both look hard at me. The little one returned to his book, grumbling, his finger running down the page. That’s when it hit me. The thing that I felt but couldn’t name till then. White. Everything on the place is white. Whitest house I’d ever seen. Tall white columns. High white walls. White shells in the road. Big boulders painted white set here and there along the road, leading up to the house like they mean to catch you if you get too close. A white horse standin in the field out back. Come to think of it, these two fellas head to foot dressed in white.

“Percy,” the little man said without looking up. “It says it right here.”

“And I say I don’t want to hear of it. I won’t have it, and you know I won’t!”

The gentlemen were in the middle of some dispute which they hoped I could settle, but now they saw I couldn’t help ‘em they looked crossly at one another. The tall thin man leaned against a pillar and stared off and the little one shut the book and folded his arms across his chest.

“I will not have it,” he said. “Our daddy would not have it and neither would his daddy.”

“It is science,” the little one began as if to explain, but the tall one cut him off.

“To speak another word of it, Perry, it’s an abomination! An abomination!”

The little fella turned on his heels and walked inside, slamming the door behind him. I started to call the General from the garden when Mr. Perry, the younger brother, spoke up.

“Don’t mind my brother, son. We have endured a hard loss in the death of our auntie, and it has put us in mind of the end of all things. Now, my brother only thinks about his end times though he’s still a young man.”

Now, these fellas was my daddy’s age if they was a day, and my daddy was not a young man in them days even.

“He thinks only of his final days,” he said. “And the ceremony for his own burial day. As you can see, he will not abide a single black thing on the place.”

He hushed his voice when he said the word. “Will not abide it, and he torments himself with the thought that some guest in honor of his passing will don the color of mourning against his wishes. I try to tell him he need not worry—that he’ll be beyond the care of such things, but he will not have it. We thought we might settle the issue by looking in this here book, but our Latin studies was too long ago. When he saw you on the road he hoped you might help us.” He looked down at the gate and the wagons traveling the road.

“Why not have a rehearsal?” I said. “My daddy belonged to the lodge and whenever they know a member is traveling the men look to the wants and desires of the fella by way of music and such. And they practice beforehand to get it right.”

My daddy always said the living need light and the dead need music. He also said ain’t nothing like laying on a cooling board to make a man’s wishes ignored, but I didn’t pass that on to Mr. Perry.

My daddy always said the living need light and the dead need music

“Oh, I knew there was a reason my brother called you!” he said. “Brother! Brother! The young man has come up with the solution,” and into the house he went, slamming the door behind him. I called to the General and was ready to walk off when the two came back outside. “Oh, young fella, young fella,” the skinny brother said and hugged me tight. “You brilliant boy! I knew it! Saw it as he was walking up the road!”

They insisted I stay on for all the preparations. Said they would have a feast and call all of their relations to make sure all went well when the real time came. Oh, they was happy.

Well, they did just as they said—would follow Mr. Percy’s last wishes. And while the arrangements were being made—the mortician and barrel maker set to making a coffin for Mr. Percy’s body, the dressing of the windows, the hiring of five white horses from Jackson to go with the one in the field, the food prepa- rations—while all of this was going on, Miss Millie, the housekeeper for the place, steady giving me the stink eye like she smell a rat. But the gentlemen had given their orders, and Miss Millie was bound and obliged to obey so she set me up with the finest foods in the grandest wing of that grand ole house. The General too. I tell you no lie—even the General got a taste of things the governor of Mississippi himself be happy to set down to, we had it so good!

But before I finished the last bite of this fine meal, housekeeper Millie learned how to keep me tied to her apron: she dragooned me for a kitchen help. Asked me what I knew about kitchen work so I asked her what she knew about dogs—seeing how I had little interest in the subject. She gave me a sharp look and that was that. I was corralled. A full day’s work. I learned more than I ever wanted to ‘bout funeral fare. She had me in it up to my ass! Tomato aspic, fried chicken, stuffed eggs, butter beans. She took a bushel of eggs and spelled out “Walker” on the big ole serving table, and me steady following her kitchen orders and itching to break free and walk the place.

I drew the line at stirring up a batch of banana nut bread. When the houseman come by to see if I could help him with arranging the table and setting out the silverware and such, oh, I got in the wind!

Hitched my wagon to his long enough to break free of Miss Millie, and got in the wind. Her eyes burning a hole in my back. Well, after I finished helping the houseman, me and the General just roamed the place top to bottom.

And you know what? Every book in every room was covered in white. And they had one room full of these little men dressed in white sitting at little desks, facing the open windows. And on each desk a white sheet of paper, and carved on each desk was, “Look thee into thine heart and write!” I didn’t know what to make of all of this so I stood by and watched from behind a bookshelf to see what all these fellas was about. Every now and then I’d see a man ring a little bell from the corner of his desk. After he rang the bell, he’d get up and lean out the window, pen and ink in hand, and write on the paper. Then he’d go back to his seat and start writing in these big white books, then looking over at the pad he’d written on at the sill. While most of the white-suited men seemed to ring a bell before they went to the window, some of these fellas just raised a tall white feather high above their heads, and then leaned out over the sill so that the room was full of tinkling bells and feathers floating about.

Of course, I wanted to find out what all of this was about, so I went around to the garden. And what did I see? Little boys of about ten years old sitting on little stools. I waited till I heard a bell, and watched as somebody sitting under the window lifted a book high over his shoulder without raising his head. Then I saw the men leaning over and copy something out of the book and disappearing from the win- dow. Quite naturally this was a puzzle to me, and first chance I got I went over to one of these boys and asked the meaning of these strange events. The boy asked me if I had come to spell him. Seems he had been waiting for some time for a chap to take his place in the raising of the little book. When I said I was a guest of the two gentlemen, he shrugged his shoulders. “Sure you ain’t here to spell me?” he said. “I got to go to the bathroom something awful.” So I made a deal. I’d take his place and let him run to the loo if he promised to tell me what was going on. He agreed. “I got a bell ringer, so if you hear it just raise the book up over your head,” he said. “and I’ll explain when I get back.” Off he ran and no sooner was he gone when I hear ring ring. So I lift up the book and hold it there for what musta been five minutes it seemed like, until he rang it again. By then the boy was back and we changed places, and it was his turn to keep his word.

“Well,” he said, ‘Mr. Percy takes powerful to his books. Got, must be, a thousand of ‘em. But he won’t have nothing black on the place and this here”—he displayed the pages of the open book to me—“full of nothing but.” And just as he said, the book was full of words in black ink like ants running across a page. “So the fellas inside, they copy down the words in blue ink mostly, though Henry”—he shrugged his shoulder towards a soft-hatted boy across the garden—“he got a fella crazy for brown.”

“But you boys still got the books out here in the garden, and the garden is on the place,” I said.

“True enough,” he said, “but we ain’t in the garden strictly, not by Mr. Percy’s lights. Cause of these.” He pointed to little white crates that his feet were perched on. It was the same with all the boys up and down the row. “If we sitting on the stool and got our feet on the crate he say we ain’t rightfully on the place.”

It was the same all over. The Walkers, for that was their name, had done everything they could to keep anything of the forbidden color off the premises. Of course, I was the blackest thing on the place, being light skinned of a light-skinned mama and a daddy the color of midnight. You take the average Black man off the street and ask him what I am he bothered you even asked him—he don’t need half a second to see something clear enough to a babe in his mama’s arms. Whiteman look all day long still can’t see. I coulda come out looking just like my daddy before me, but they ain’t know that so I took my ease walking the garden and the halls of those two fine gentlemen.

Finally, the day arrived, and all the relations had gathered round, all dressed in white the way Mr. Percy wanted. The mayor of Natchez and your various and sundry muckety-mucks from the town came. They all gathered out front, lining the walk. I was there too, outfitted by the gentlemen as an honored guest. My black soul hidden by the fine clothes given me by the brothers. And down the road come six white stallions leading a white wagon. It pulled up and six cousins unload the coffin from the hearse and carry it up the winding walk. Mr. Percy’s laid out and don’t he look like all goodness and mercy with a satin pillow under his head? He was the belle of the ball. Little children were singing from the portico as the coffin was carried into the house:

Safe in his alabaster chamber

Untouched by morning

Untouched by noon . . .

It looked like there was a tiny smile on Mr. Percy’s face, but that musta been my imagination. Well, they laid him out in the grand hall and dinner was served for Mr. Percy not only had an eye toward heaven, but he thought waste a terrible abomination, and meant to combine feast and funeral so that he need not put up overnight those guests who had traveled from far away. So the reverend he blessed the food and we all sat on three sides of the room with Mr. Percy laid out in the center so everybody could see him and he could hear everybody.

The reverend blessed the food, and it’s a fine meal. Miss Millie did herself proud. Ham and potatoes, chicken fried just right. Well, I’m eating with the young’uns, and Mr. Percy’s relations sitting on all sides around me. Then Mr. Perry stood up to speak and say how the passing of their auntie put Mr. Percy in the mind of final things. That’s when Mr. Percy clears his throat to correct Mr. Perry, but Mr. Perry didn’t catch it right away so Mr. Percy commence to clear his throat again, but he ain’t moving, just steady laying there. Finally, Mr. Percy clear his throat so that folks way down at the Natchez landing must have heard him, and Mr. Perry understands that he has to conduct the ceremonies properly as if Mr. Percy truly was dead and gone.

So, he began again. “He was a man before his time like our daddy and his daddy’s daddy before him. He upheld the sign and symbol of what it meant to be a Walker: truth, integrity, and work. He would have prospered even more as the world accounts prosperity if he did not uphold the Walker family tradition to avoid close association with anything ebonine”—All the sudden, up pops Mr. Percy’s head out of the coffin, his eyes wide. Mr. Perry knew he done wrong then, speak- ing the word, so he tries again, clearing his throat now, and Mr. Percy eased back down real slow, and closed his eyes.

All the sudden, up pops Mr. Percy’s head out of the coffin, his eyes wide.

“From his daddy’s daddy to now we know that the bondsman was nothing but an unrelieved misery imposed on the southland. And Mr. Percy took it upon himself to eradicate in sign and symbol all such elements from the Walker family holdings. For such devotion, he was rewarded with a large and loving family as you see gathered here today and the respect and admiration of all in Natchez and all the county.”

Didn’t Mr. Percy blush at that? And his relations liking what they hear, and Mr. Perry warming to his words: “Oh, yes, he was generous and never niggardly with his workers . . .” And up jumped Mr. Percy, eyes wide open and displeased. Seems he objected to the word, and Mr. Perry, who had worked himself into a commotion, took offense at this second interruption.

“You are forsworn to avoid all talk of”—“But I didn’t”—“You did”—“I did no such thing and I can prove it.”

Mr. Perry called one of the little barefooted chaps at the end of the table to fetch him a dictionary, but the poor fella was too young to understand any of these goings on, and began to cry when he saw a dead man rise up not once, but twice while he was eating his dinner, and ran to his mama in tears and threw himself on her bosom.

He was leaning over the side—he couldn’t believe what he was seeing: every single one of them hogs was black as night.

So Mr. Percy sent his butler to fetch the dictionary when in come relations from up north. Seems they had been delayed and only just now had arrived at the landing at Natchez Under the Hill on a ferry from the Arkansas side of the river. Well, these cousins, a thin, elderly man and a stout, elegant matron, not only did they arrive late but the message had gotten confused in the telling, and they thought they were coming to attend the real live funeral of Mr. Percy who they thought dead, and he was dead seeing how he was laid out when they walked in the room. But when that old matron saw him rise up like that? Well, down she went, pale as that coffin. Half the room run over to tend to her. The other half rise up to comfort the squalling children, several of which seemed to cry just cause they saw the first one crying and maybe they didn’t want to miss out on the fun. Just when Mr. Percy had rose up in his coffin, huffing and puffing, there was a terrible racket outside the window, sound like the Lord casting evil spirits out of swine. I get up to see what it is, naturally, and ain’t it the most confusion since the Tower of Babel? Hogs everywhere! A wagon had hit that ditch and bam! Out tum- bled the hogs. They running up and down the road, and into the Walker yard, running up the steps as if they was running from the devil himself.

That’s when Mr. Percy’s butler opens the front door to see to the com- motion, and didn’t them hogs run right over him like he a country road? They burst into the room, and it looked like Mr. Percy was gone have the stroke for real! He was leaning over the side—he couldn’t believe what he was seeing: every single one of them hogs was black as night. They rooting around them turnips that spell out the family name, fighting for the choice ones they nearly topple over the coffin with Mr. Percy in it!

Now, I had left the General out in the garden tied up to one of them little crates. One, because it would be rude to have the General traipsing about during such a solemn occasion and two, the General was a fine, obedient dog: you say stay, he stays. You say come, he comes. He was a fine dog except for one thing: he just can’t stand the sight of a reverend. Never could. He see a reverend coming down the road, toting the good book, he gone break his neck trying to get away like Old Scratch coming for him. Well, maybe he thought his days of running was up, that he’d run as far and long as he could from the reverends of the world, and now he meant to stand his ground. More even. When those hogs got to busting in the place he jumped up and over the threshold and into the great hall, bearing down hard for the reverend. He must have spied him at the head table, cause he broke from the garden with that old crate trailing right behind him. I think the reverend must have seen him out the corner of his eye cause as soon as the General came through the door, the reverend was up and run-ning. The General chased him round and round the room, that crate crashing into chairs and sending old matrons and the mayor himself dancing on tabletops, trying to get clear.

Meantime, Mr. Perry’s wading through them hogs like high water, and Mr. Percy in danger of drowning.

I finally caught the General, but by then it was too late. The reverend made two rounds of the room, and on the third he went right through the open door and kept getting up! I think he must have run till he got to Natchez Under the Hill.

Meantime, Mr. Perry’s wading through them hogs like high water, and Mr. Percy in danger of drowning. He scooped him up just before them hogs knocked the whole thing over, so happy they were to get at them radishes so that nothing but the W was left. Mr. Perry carried his brother through all the boys and girls crying and wailing to his bedroom, and laid him out just like a little baby boy.

They sent everybody home and Mr. Percy is feverish, talking in his sleep, and saying over and over again something I couldn’t understand, so we left him to rest. He slept for almost twelve hours till we heard shouting and we all hurried to see what was the matter, and there was Mr. Percy naked as a jaybird all covered in black soot! He had taken a charcoal from the fire after it burned out and smeared it all over hisself, and all over the walls he had written nigrum, nigrius, nigro. Mr. Perry called Miss Millie and together they bathed him and put him back to bed, but Mr. Percy wouldn’t be parted from me. Even before he laid up for twelve hours he made Mr. Perry promise to keep me on. I sat by Mr. Percy and he had something burning in his eyes to speak like he had seen something in his dreams and he meant to tell it.

He set me down by the fire like I was his own boy and began to tell me the story of his people. He wouldn’t allow nobody, even Mr. Perry, to come near.

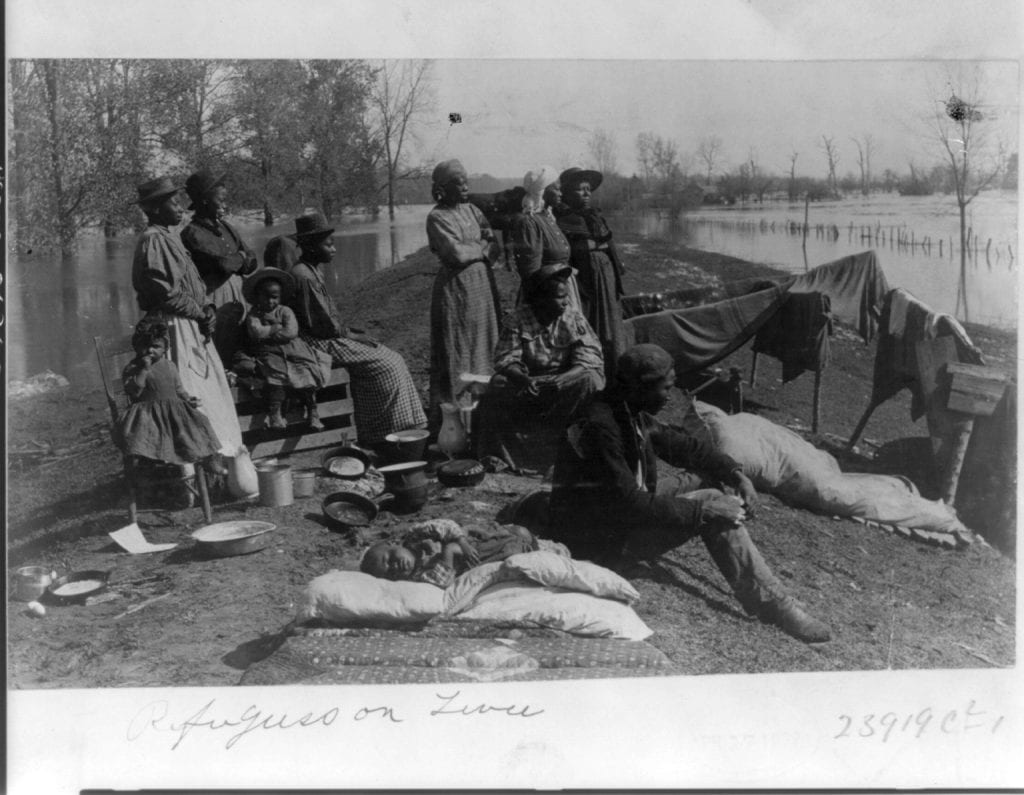

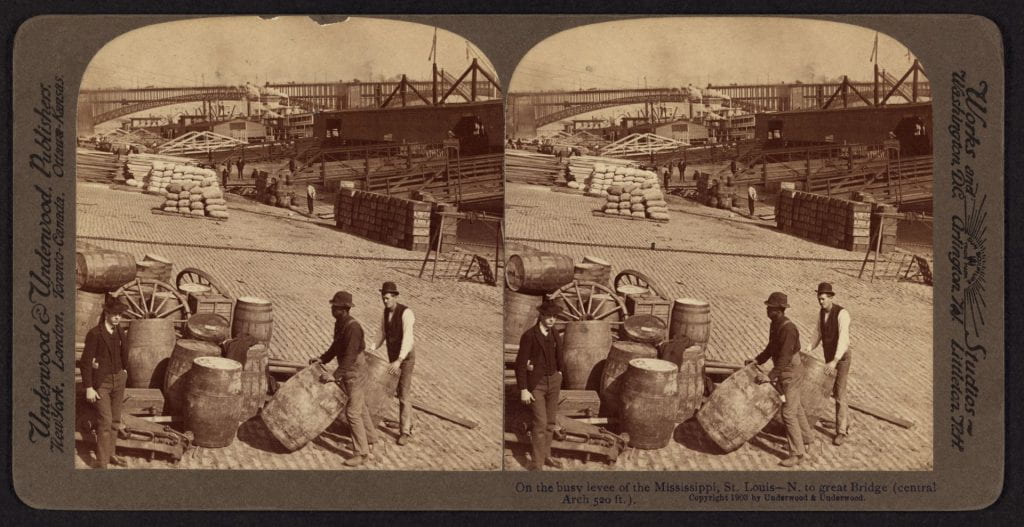

He said after the war his granddaddy worked to keep the scalawags out the county and keep what he called the rightful place of the planters. He ran a contract firm to build the levee after it had been ruined by the war. One day, there was a rise, and the levee broke above Natchez. He said there were rough men on those levee camps. Twenty-five to one was the ratio a whiteman faced. Well, when the rise came his granddaddy had the governor call up the state militia to make sure all the labor didn’t run off. Well, after a while cholera rise up on the levee, but the guard was told to make ‘em stay, and make ‘em stay they did. Well, one of the leveemen had his wife out at the camp, and she was heavy with child. He waited till dark, took a little skiff, meaning to carry his wife north to the doctor. Well, he made it past the militia, them not being rivermen, they passed right by ‘em, but his granddaddy and his man kept a sharp lookout. Anybody traveling by night near the levee liable to get shot for fear some contractor from the Arkansas side try to blow a hole in the Mississippi side to take pressure off his. Well, his granddaddy threw a light on that little skiff, and the man raise up, toting a rifle. The leveeman said his wife was ready to bear his boy, and he meant to carry her to the doctor. Mr. Percy’s granddaddy said: “You shall not pass.” Even though the man said there was cholera on the levee. His granddaddy would not have it. He said if he let that man off the levee he gotta let ‘em all off. Well, the man backed off, all right, but he returned with two other skiffs full of men, and as soon as his granddaddy threw that light on ‘em, them skiffs opened up. Old George, his granddaddy’s man, was dead before he hit the ground. The old man was hit in the shoulder.

Well, that started three days a war on the levee. Those men fought to get off it, and Old Man Walker and his men fought to keep ‘em on it. Not one of ‘em got loose as far as he could tell. Some escaped to the Arkansas side. He said they hunted ‘em down. From that day his grand- daddy said those men were an unrelieved misery on the southland—the way it made a man be. Said he’d never work a levee crew again less it was a whiteman. He worked Irish exclusively until he couldn’t make a living off the river anymore, and he and his brothers went back to growing cot- ton. Mr. Percy looked at the walls and the shadows—night was coming on, and the fire brightening the room. He had this little picture of Paul on the road to Damascus in a gold frame near his bed. Then he said that just before Old Man Walker died, the old man went out of his head.

His granddaddy started talking about the three days on the levee. Kept saying how they hunted those fellas down. Every last one of ‘em. Then Mr. Percy said something strange happened, something he didn’t understand. He said it was like it wasn’t his granddad anymore. Mr. Percy said he looked like a baby, and at the same time like a worm. His eyes was wide open, and he was calling for his wife, Mr. Percy’s grandmother, but only Mr. Percy was in the room. Everybody else had stepped out. Just for a moment, Mr. Percy was alone with him. His granddad lay there, and called for his dead wife, asking her to tell him who he was now that the men on the levee were gone. Tell him who he was now that they were gone. Mr. Percy said he had that baby-worm face and was grabbing at the bedclothes. Then he died, and they hung a drape across the mirror.

I stayed on for a few more days. Mr. Percy insisted. He sent all them boys home, and the men in the little white suits too. Said he’d let death come on. Said the night comes on, so he’d let death come on too when it was good and ready.